Employment in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: A Call for a Statutory Solution

Brandon Ward[1]*

Like the automobile, computer, and the internet defined the twentieth century, artificial intelligence (AI) will come to define the twenty-first century as it branches out to influence all aspects of humanity. One area that undoubtably will be shaped by AI is employment. Companies are racing to integrate automation, machine learning, and deep learning, all sub-processes of artificial narrow intelligence, into routine tasks or into the analysis of large data sets. In time, many of those tasks that humans have come to dominate will shift to machines, leaving many without the means to earn a living, pay bills, or contribute to the economy. Although experts disagree on the full extent of the impact of AI on the near-term or long-term employment prospects for mankind, the general consensus is that AI will definitely eliminate some jobs that humans now occupy. Unlike prior economic crises, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s or the Great Recession of the late 2000s, this will be a crisis created by our own ingenuity and innovation. We have the opportunity now, and certainly the impetus, to shape economic, labor, and educational policy on a national scale to mitigate the worst potential effects of workplace automation—mass unemployment followed by restless and hopeless citizenry unable to elevate themselves. This paper offers models for a statutory solution.

First, this paper explores the potential impact of AI on workforce automation in the near term, or the next ten-to-twenty years, with an eye on the long-term effects on employment. Second, current social safety systems, such as unemployment insurance, bankruptcy protections, and local and community support will be wholly insufficient, and likely overwhelmed, to absorb and reorient unemployed individuals into other forms of work. Finally, this paper argues that the best possible way to mitigate the negative effects of AI-enabled task automation—the loss of human employment—is to implement legislative action that will profoundly alter the socio-economic contract between the government and the people. Consistent with progressive initiatives in the 1930s created to provide workers greater protection in their unequal position with employers, and similar to Congressional action to reintegrate millions of service members into the economy following the Second World War, legislation now must redefine government’s role in assuring the populace of opportunities to continue to provide for themselves. This paper offers statutory models for necessary legislation that ensures workers displaced by automation are provided opportunities to seek new skills that will be necessary in a future dominated by AI.

The Artificial Intelligence Problem

Artificial Intelligence Defined

Artificial intelligence (AI) is far more complex than meets the eye. According to Merriam-Webster, artificial intelligence is “the capability of a machine to imitate intelligent human behavior.”[2] Unfortunately, this simple definition does not fully grasp the full potentiality of AI and is omissive at best. The internet is replete with theories as to what AI is and can be but these notions essentially break down into three concepts based on predicted capability: Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI), Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), and Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI).[3] ANI is the most basic kind of AI, AGI is essentially the equivalent of human intelligence, and ASI is far beyond the capability of human thinking.

ANI already exists—think of modern digital assistants such as Siri, Alexa, or Cortana.[4] These systems combine machine learning and vast troves of data to mimic human thinking in narrow applications.[5] ANI is far less capable than the average human mind but can imitate some human capabilities in limited scope, such as “checking the weather, being able to play chess, or analyzing raw data to write journalistic reports.”[6]

AGI closely mirrors human intelligence. If ANI represents a limited application of human intelligence to a specific problem, AGI is the machine equivalent to a human brain, capable of the range of emotion, cognition, and intellectual capacity of an average human. Although this paper touches briefly on the possible effects of AGI, it largely proposes to address the consequences of mass disruption to the workforce as people are replaced with thinking machines to produce work, which is happening with the proliferation of ANI and would likely accelerate with AGI. ASI is the last stage in the evolution of AI and will occur when a machine is more capable than human intelligence.[7] Although much debated in the scientific community, if this stage were to come to fruition, human employment will no longer be a consideration.[8]

The Next Productivity Revolution

Humanity has experienced three major productivity “revolutions” over the last 300 years.[9] The First Industrial Revolution began in the United Kingdom in the eighteenth century and continued to the early twentieth century as its effects spread across the world.[10] During this period, technology transformed working conditions and employment in profound and lasting ways.[11] New and improved methods of agriculture and industrial processes amplified productivity to unprecedented levels and freed millions from subsistence employment, but not without unintended consequences.[12]

The Second Industrial Revolution erupted toward the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries as industrial processes combined with automation, interchangeable parts, standardization, and assembly lines.[13] Industrialists increased productivity, drove down costs, and consolidated markets to generate untold wealth, often concentrated to a relative few at the expense of the laboring masses.[14] The Third Industrial Revolution began in the mid-twentieth century with the advent and proliferation of computer systems and their offspring: robotics, automation, and big data.[15] According to some leading economic theorists, we are on the cusp of another industrial revolution in which all prior progress will be amplified exponentially with the creation of AI.[16]

In all previous industrial revolutions, labor and capital were profoundly transformed. And, in each iteration, the balance between labor and capital shifted toward capital with the advent of new technology.[17] As mentioned above, the First Industrial Revolution saw farmers and agricultural workers move into urban areas and participate as labor in manufacturing, among other activities.[18] Up to this point in history, agriculture was primarily a subsistence activity, with the exception being large-scale farming operations driven principally by slaveholders in the United States or by state-sponsored corporations subjugating native populations in other parts of the world.[19] In this context, the value of labor to income greatly exceeded capital. When farmers became industrial workers, they “sold” their labor to others who profited from their investment in capital.[20] Labor was necessary to turn the cogs, run the assembly lines, and oversee the work but capital was essential to create the factories, build the machines, and establish infrastructure.[21] As a result, national incomes shifted from labor to capital, real wages stagnated, while gross profits soared.[22] This process has played out in subsequent industrial revolutions and is likely to continue, if not accelerate, in the next stage of our economic progress.[23]

Unlike prior industrial revolutions, mass adoption of AI has the potential to eliminate substantial employment.[24] In the First Industrial Revolution, subsistence farming gave way largely to manufactory or other labor-intensive work.[25] In the Second Industrial Revolution, workers transitioned to assembly lines and machine-assisted tasks.[26] In the Third Industrial Revolution, workers transitioned to more service-oriented positions to capitalize on the benefits of automation and data.[27] In these three prior industrial revolutions, the workforce largely shifted to compensate for technological changes with consequent social and political upheaval.[28] However, it is unclear what effects AI will have on the workforce. Some predictions foresee AI replacing nearly fifty percent of the workforce in the next fifteen-to-twenty years.[29] Others predict that, in concurrence with past industrial revolutions, people will find new lines of work and the negative impact on the workforce will be minimal.[30] Although it is impossible to know what the future holds, if AI progresses to the point of reaching AGI, the latter prediction seems less plausible given the outsized power of capital. Due to costs associated with labor, such as the need to grant rest breaks, sleep, compensate for fatigue, and workplace injury insurance to name just a few, an entity is more likely to put emphasis on capital rather than labor.[31]

Who Wins and Who Loses When AI Takes Over?

The First Industrial Revolution brought forth individuals who profited on the shift in economic power from labor to capital to build fantastic wealth: John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan, to name a few.[32] Derided in the popular press of their time as “robber barons,” these men took advantage of economic forces that greatly rewarded capital over labor.[33] In subsequent industrial revolutions, others have profited similarly from tactful investment of capital, such as Henry Ford, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett. The power of capital accelerates at a precipitously faster pace than labor at each industrial revolution which has led to massive wealth disparities amplified through state-lauded technological innovation.[34] In the next phase of our technological development, as AI is more widely adopted throughout economies, capital will continue to rise in prominence, greatly benefiting those who control the capital, while labor will likely play a diminishing role.

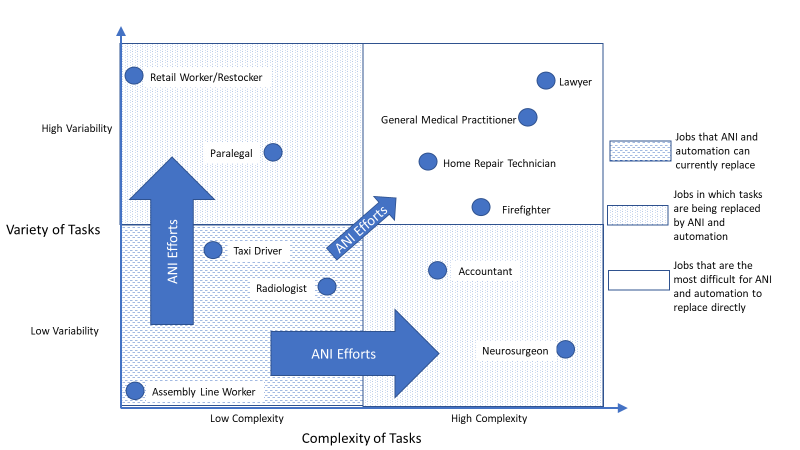

Virtually all segments of the workforce will likely be affected by AI, especially if AGI is realized.[35] All employment can essentially be divided into a four-quadrant diagram with the vertical axis representing the variety of tasks associated with the employment and the horizontal axis representing the complexity of tasks.

Figure 1[36]

Figure 1[36]

The lower left quadrant represents occupations that have a limited number of tasks of low complexity—think assembly line workers. Jobs in this quadrant have already largely been replaced by automation and ANI. The top right quadrant represents jobs that require a variety of tasks of high complexity. Lawyers, for example, would fall into this quadrant. The top right quadrant is likely safest from AI encroachment due to the limited ability of ANI at present, but this may not always be true. Even lawyers, or at least some of the tasks that lawyers do, are under threat from AI.[37] The top left quadrant represents jobs that have low complexity but a high variety of tasks, such as a retail stocker. Finally, the bottom right quadrant represents occupations that require a limited number of tasks but are highly complex. Some highly specialized medical practitioners, such as neurosurgeons, would fall into this quadrant. It is in the top left and bottom right portions of this diagram that AI is making its greatest push. In fact, some jobs thought to be immune from automation, like those intimately involved in human interactions, such as doctors and nurses, are now in the crosshairs.[38]

If we create AGI, the “winners” will be those who own the capital. The “losers” will be participants in the labor market. Barring that dystopian scenario,[39] there will likely be some kind of transition where many jobs, if not all, are affected in some way by ANI as processes and systems are further routinized and automated.[40] In an ANI-dominated economy, participants in the labor market may avoid being “losers” by learning new skills, integrating technology into their own processes, and accumulating their own capital, but these options will likely be limited to those who can afford them.

Current Social Safety Systems are Inadequate

If the United States does not act quickly, the workforce most directly affected by AI will be at the mercy of our social safety systems, which are wholly inadequate for the task. State-sponsored protection systems such as unemployment compensation and bankruptcy law will not be enough to absorb the consequences of massive disruption to the workforce. Further, company-provided benefits packages, such as severance, are applied at an uneven and insufficient rate to be of much help to the broader population of people who will likely lose their jobs, despite some state efforts to mandate severance.[41] Local action, likewise, will be insufficient to assist mass numbers of unemployed workers in a transition. In some limited circumstances, efforts to alleviate local issues caused by unemployment have been somewhat successful.[42] However, when thirty-to-forty percent of the workforce is facing unemployment (and that may be on the low-end of predictions), even applying the totality of community resources will not suffice. A national response is necessary.

Unemployment compensation, conceived under a mishmash of compromises between competing political interests at the time, is incapable of absorbing and softening the blow to society that will come from the mass of future AI-rendered unemployed.[43] Although created by the Social Security Act of 1935, its main effect was to incentivize states to create their own unemployment compensation eligibility systems and administer the programs on behalf of the federal government.[44] The basic premise is that employers must pay into these insurance programs on behalf of each employee and these payments serve as the basis for compensation to any unemployed and eligible citizen in a state that participates in the program (all states participate).[45] These payments turn into deposits that the federal government shares with states which, in turn, determine unemployment eligibility and administer the program in line with federal guidelines.[46] The Department of Labor provides the general direction for the program.[47] The terms of unemployment compensation vary from state to state, including payment period, amount of compensation, and requirements imposed on eligible unemployed citizens to continue to draw benefits.[48]

Even though the program was envisioned to combat the unemployment crisis during the Great Depression, its initial rollout was hampered by delays and ineffective management, limiting an assessment of its effectiveness in its purpose.[49] The real resolution to the Great Depression, which, at its height, saw nearly twenty-five percent of the working population out of jobs,[50] came from the massive nationwide mobilization to support the military in World War Two.[51] Since the Great Depression and before the Global Pandemic of 2020, the highest the unemployment rate has reached was 10.8% in November and December 1982.[52] Even during the Great Recession in 2009, the unemployment rate only briefly touched ten percent.[53] As of the writing of this article, the unemployment rate reached an all-time high since the Great Depression, 14.7% in April 2020, caused principally by layoffs and furloughs in response to measures to stem the spread of coronavirus, which causes COVID-19[54]—a disease affecting respiratory processes that is particularly harmful to the elderly and those with underlying health conditions.[55] Despite congressional attempts to alleviate the strain on the unemployed caused by the U.S. response to the Global Pandemic, it is unclear what the ultimate impact on the workforce will be.[56]

In past high-unemployment periods, laid off workers tend to exhaust the limited unemployment compensation benefits under federal and state programs.[57] For example, in July 2009, nearly fifty-one percent of participants exhausted their twenty-six-week benefit period due principally to the difficulty of finding a new job in a labor-saturated market.[58] Once benefits are exhausted, the unemployed are often left to the mercy of family, friends, or other social safety systems, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), otherwise referred to as welfare, which is designed to keep people from slipping into the lowest rung of society.[59] Unfortunately, the return rate from the bottom of the social ladder is quite low and decreases the longer an individual remains in poverty.[60]

If unemployment compensation systems struggle to bridge difficulties for unemployed under an unemployment rate of ten percent, the system will certainly fail when thirty-to-forty percent of the workforce is left unemployed (or unemployable) once AI, namely ANI, is widely adopted. This seems to be the perfect storm of conditions to rend social safety systems designed originally as a catch for employees in a largely “at-will” employment market to complete collapse. What precipitated the unemployment compensation system as it exists now—the Great Depression—was the kind of catalyst necessary to jolt Congress into action. Unemployment compensation may have been a logical solution catered to the needs of the time when it was created, but it will simply not work as it currently exists when the AI disruption begins.

Bankruptcy Courts Will not be able to Handle the Surge

Unemployment consistently contributes to bankruptcy.[61] On average between 2006 and 2017, just over one million people entered Chapter 7 or Chapter 13 bankruptcy each year.[62] During the period between 2008 and 2013, the period most profoundly marked by the Great Recession, this average jumped to 1.265 million per year.[63] During the Great Recession, unemployment rates reached highpoints not seen in nearly thirty years.[64] The connection between unemployment and personal bankruptcy, although susceptible to influence by other variables, is clear.[65]

According to historical research, nearly two-thirds of individuals entering bankruptcy did so due to an employment-related issue, such as termination, demotion, or forced transition.[66] Such a strong connection to unemployment has led to research that proposes that a ten-percent increase in the base unemployment rate leads to a fourteen-percent increase from the base personal bankruptcy rate.[67] The personal bankruptcy rate is computed using the total number of individual (non-business) filers divided by the population.[68] So, if one million individuals filed for bankruptcy, that represents a personal bankruptcy rate in the United States (population of approximately 328 million as of July 2019[69]) of .3%. Extrapolating from the Demirkan model, if the unemployment rate rises from a base of five percent to thirty percent, the increase over the base is a whopping 600%. Under this scenario, the corresponding personal bankruptcy rate would then rise by 840% over its base. If the base is currently one million personal bankruptcy filings per year, then the new personal bankruptcy rate under a thirty-percent unemployment model results in 8.4 million Americans filing bankruptcy each year. This is an astronomical figure, and one with which the courts will undoubtably struggle.

Severance packages offered to employees who are subsequently terminated for any reason, outside of “for cause,” are generally rare and often only available to the higher strata of the workforce.[70] There is no federal law that mandates severance pay.[71] Some companies enact severance programs as part of compromises with organized labor or as part of a genuine concern for the social security of their workforces.[72] Whatever the motivations, however, severance systems are similar to unemployment compensation in that they are primarily intended to assist the affected employee to bridge the income gap between jobs.[73] Meanwhile, employers are often free to make such payments contingent on employees expressly agreeing not to hold the employer liable under contract or tort claims.[74] Such agreements are often enforceable in court to the employer’s benefit, but may not always be so, especially in cases where the employer secures a waiver from an employee who may have a claim for discrimination.[75]

The notion that employers, through distribution of severance payments to employees made unemployable by AI, can fill the void as an alternative to a government-mandated compensation system defies logic. Severance as a concept is negotiated through agreement and, like in all negotiations, parties have differing motivations to reaching an agreement.[76] Employers are motivated to pay less than fair value for the employee’s contribution and employees are motivated to seek more than they are owed.[77] Similarly, employers value severance in a different light than do employees.[78] These competing perspectives necessitate a fair and neutral arbiter.

New Jersey recently became the first state in the nation to mandate severance for employees who are subject to mass layoffs.[79] Senate Bill 3170 requires “businesses with 100 or more full-time employees pay their workers one week of severance pay for every year of service whenever widespread downsizing or plant closures affecting 50 or more employees is on the horizon.”[80] Although certainly a step meant to provide for employee welfare, a large section of total employment in New Jersey belongs to organizations that employ fewer than 100 employees, rendering such a step largely symbolic.[81] In fact, legislators wrote the law principally to rebuke the acquisition practices of one kind of business model: private equity.[82] Even though it is unhelpful to a huge portion of the workforce, New Jersey’s new statute provides inspiration to other jurisdictions to implement similar provisions against large multi-state businesses operating in their borders.[83] A national, standardized, memorialized-in-statute, solution would be a better option.

Local Responses will not be Sufficient

The Workers’ Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act of 1988 was a result of analysis of the local effects of mass layoffs on communities.[84] The act requires that eligible employers provide, among other requirements, certain notices to community leaders prior to large-scale terminations as a means of encouraging local mobilization of resources to absorb the consequences of employment loss.[85] Unfortunately, exemptions to the notification requirements essentially mute the law’s intended purpose, and the mobilization of resources to blunt economic harm often are insufficient.[86] However, in some limited cases, such as in Janesville, Wisconsin—following the closure of a manufacturing center—local communities have attempted to minimize the harm of mass layoffs when neighbors, community and local government leaders, religious and charitable groups, families and connected social networks mobilized support to affected members.[87]

Although local and community connections may provide a degree of success for people in search of a job,[88] the long-term recovery from a large-scale loss of employment seems to hinge on circumstances beyond the capabilities of various well-meaning community groups.[89] Interest rates, foreign investment and trade, business and economic trends on the international and national level, and other macroeconomic forces may be just as important as national policy choices when it comes to job recovery.[90] The circumstances and resources brought to bear that allowed Janesville to survive the loss of a major employer are unlikely to exist in the thousands of communities across the country. States, as extensions of these local communities, are wholly unprepared to absorb the loss of thirty-to-forty percent of jobs in their borders.[91] Therefore, a national initiative will be necessary to ensure uniform protection across the country when AI may leave entire communities bereft of employment opportunities.

A Federal Statutory Solution is Necessary

Much of the protections employees now enjoy were born as a result of the greatest social and economic disaster of the twentieth century—the Great Depression.[92] This crisis led to nearly twenty-five percent of working age adults being left out of work in 1933.[93] As the United States and other countries grappled with severe unemployment and economic conditions that stifled recovery, workers, both employed and unemployed, voted for politicians who would directly confront the crisis and work to prevent its recurrence.[94] Franklin D. Roosevelt, campaigning on a revitalized social welfare program, became president in the same year as the height of the country’s unemployment rate.[95] The Democratic administration worked with Congress and drafted legislation to provide some protections to the workforce in general.[96] After much compromise, and some resistance in the Supreme Court as to the constitutional limits of such legislation,[97] workforce protections enacted in the Social Security Act solidified across the country and have been relied upon by countless citizens since.[98]

A great financial disaster and its subsequent horrible effects were the necessary catalysts to jolt leaders into action in the 1930s—with some horrifying results.[99] We are quite possibly at the precipice of another economic disaster of our own creation.[100] AI will undoubtably impact the workforce in ways that are unpredictable, ranging from automating routine tasks to make workers more productive to simply replacing humans in the workplace.[101] Some economic theorists believe that the workforce will adjust and shift to new lines of work, much as the workforce has done in previous industrial revolutions.[102] However, scholars and AI experts differ in theories as to what jobs will be necessary in a future workforce dominated by AI.[103] What is certain is that for the workforce to make this adjustment, worker flexibility and adaptability will be necessary.[104] Due to the potential for massive disruption in a relatively short period of time, government should act now to prepare the way for workers to become flexible and adaptable to future work needs.[105] Our current systems will not be sufficient to overcome the challenge of transitioning a huge segment of the workforce into future work which is currently unpredictable. The time is right to enact legislation, comprehensive employment protection, and education programs akin to the broad social system restructuring that took place as a result of the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Instead of solely following the Social Security Act as a model for implementing employee protections, there is another New Deal-era program that could serve the basis for a complete reorientation of the workforce: the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, more commonly known as the GI Bill.[106] At the time of the act’s creation, the Second World War was still very much being fought in Europe and the Pacific but Congress had the foresight to envision that the vast multitudes of military men and women pulled into the conflict would one day return to the civilian sector and require employment.[107] Rather than just cut this manpower from stable military employment and leave them to their own devices, Congress provided guidance and funding to create the infrastructure that would oversee the administration of transition benefits for veterans, such as: unemployment compensation, mortgage assistance, low-interest loans to start a business, and educational assistance in the form of payments for tuition and living expenses.[108] Consequently, millions of American veterans took advantage of these benefits to learn new skills and contribute to the economy in profound, beneficial, and lasting ways.[109] Interestingly, New Deal Democrats envisioned a “GI Bill” system for all workers, especially the poor, but were stymied in their efforts by conservatives who decried that such an undertaking must be limited to veterans to save on costs.[110] Now, failure to enact such a program for all employees may prove much more costly.

For the foreseeable future, humans will be necessary participants in the workforce.[111] Predictions for the emergence of AGI vary widely.[112] ASI may never occur.[113] However, ANI has already proven to be a powerful cost-saving and productivity-increasing force.[114] Statutory solutions to the problems inherent with mass job losses should also incorporate incentives to encourage businesses to adopt such productivity-enhancing tools (as if businesses do not already have a strong profit-focused incentive) for the betterment of the whole economy.[115] Encouraging businesses to embrace more automation may initially appear paradoxical to the argument that the United States must take actions to secure human jobs. But appearances are misleading.

Automation of tasks is key to maintaining the United States’ edge in productivity.[116] Other state entities, such as China, Japan, South Korea, and the European Union, are competing hard in the automation arena.[117] Stricter regulation and financial and legal disincentives in the European Union may discount its progress in the short term, but governmental leadership in its various member-states could accelerate automation.[118] China has no such restrictions.[119] With a vast labor force and considerable financial investment in labor-intensive manufacturing practices, China’s transition to automation may seem counterintuitive; but, Chinese political and business leaders recognize that the technological and financial incentives for increased productivity outweigh labor considerations.[120] China also has the advantage as an autocratic country to rapidly steer its economic and industrial ship, unlike the United States which must act through voluntary consensus.[121] Time is not on the United States’ side.

Besides the obvious profit incentive for businesses to adopt automation as a means of decreasing costs or increasing productivity, the government should also consider implementing incentives to encourage adoption, as other nations have.[122] Possible incentives could include: tax breaks in a ratio consistent with a business’s costs to adopt technology, making severance payments associated with employees who are terminated directly due to automation tax deductible, or access to low-interest government-backed loans to finance the adoption of automation technology, to name a few possibilities.[123]

Due to the foreseeable consequences of mass layoffs on a national scale, including increases in mortgage defaults[124] and bankruptcy filings,[125] wage depression,[126] increased suicide rates,[127] etc., any legislation intending to prevent or cure those attendant social ills should address at least four key areas: (1) education; (2) support to small business; (3) housing; and, (4) a minimal basic income. Coincidentally, the GI Bill and its subsequent amendments address most of these areas.[128] Another federal program, the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program, created in the 1970s as a statutory response to mass job losses caused by globalization, provides some of the same benefits as the GI Bill but geared towards employees in fields disrupted by importation and with differing standards for petition of benefits.[129] Lastly, the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) provides some foundation (although, as mentioned above, the unemployment insurance program is wholly inadequate to solve mass unemployment disruption alone) for the administration of a benefits program that meets the basic income needs of individuals going through a transition caused by unemployment.[130] A combination of the GI Bill, along with other statutes geared toward veterans, the TAA, and the FUTA could serve as a statutory model to follow in the crafting of a solution to the foreseeable workforce disruption attributable to AI.

We do not have a firm grasp as to what jobs will be necessary when the majority of work will be done by robots infused with AI.[131] However, even in a future economy dominated by automation, humans will likely continue to perform some jobs.[132] In past industrial revolutions, workers feared that loss of jobs could not be recovered.[133] In every revolution thus far, new jobs and new lines of work arose in the ashes of the old.[134] Although AI represents a new frontier in the accomplishment of work, humans will likely have some role.[135] But, because we do not know what jobs will be necessary or in demand in the future, a key objective must be to have a flexible education system to reorient individuals with outdated skills into the new lines of work necessary to support a robot-centric economic system.[136]

Just like the GI Bill, a statutory solution to assist transitioning workers should prioritize education and skills development. The most recent version of the GI Bill, the Colmery Veterans Educational Assistance Act, otherwise known as the “Forever GI Bill,” signed into law in August 2017, significantly amended the Post-9/11 Educational Assistance Program, the veteran-focused educational system.[137] The Forever GI Bill solidifies education’s central role in the transition of veterans from military service to other work.[138] Veterans receive as a primary benefit of qualified military service a time window commensurate with their time in service to be applied towards educational attainment.[139] In order to qualify for most of these benefits, the veteran must have been discharged honorably.[140] However, active duty military members are eligible to use some aspects of the GI Bill.[141]

During the eligibility time window—ranging from as low as one month to up to thirty-six months—veterans can receive a prorated amount of financial support that can be applied to an educational program, often delineated by a percentage associated with full payment.[142] A 100% rate indicates that the GI Bill will pay up to the tuition cost at the highest in-state tuition rate for a state-supported higher education institution in a covered term.[143] Eligible programs range from the attainment of an associate’s degree up to a Ph.D.[144] Other common programs utilized by veterans include trade schools, apprenticeships, and teacher preparation programs, to name a few.[145] Most programs must be accredited by a national accreditation service to qualify for government funds, with a few exceptions.[146]

A statutory solution to AI disruption of the workforce could follow much of what the GI Bill and its subsequent amendments allow. The GI Bill calculates eligibility time frames based on the time in service of the veteran.[147] For example, a veteran who served for thirty-six months of active service is eligible for thirty-six months of benefits at the 100% rate.[148] For the bulk of the work force, a time-in-service calculation will be unworkable. Alternatively, a statutory solution could consider eligibility timeframes based on the applicant’s work history, such as what the TAA requires.[149] Other options to determine eligibility could include consideration for how long the worker has been in the workforce, how much the worker has paid in taxes, what skills the worker has already acquired, overall performance history, etc. The age of the applicant could also be considered as younger applicants would be more likely to need educational assistance again to adapt to future unforeseeable needs in work skills.[150] However, consideration of age could trigger provisions of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) so careful treading will be necessary.[151] Ideally, employees who have established consistently positive work histories would be eligible for the maximum time benefit. The GI Bill is only available to the veteran once in his or her life.[152] A statutory solution geared to help American workers overcome AI disruption should consider multiple iterations of use since future skills needs are unforeseeable and the timeframe of effective use of attained skills may be less than a lifetime.[153] This, of course, will increase the cost.

The GI Bill does not dictate what fields of study a veteran must pursue.[154] The Department of Veterans Affairs makes no judgment over what school or program a veteran should participate in, save the requirement that the program be accredited (in most cases).[155] The GI Bill imposes no mandates on the kinds of education a veteran should attain to maximize the veteran’s employability.[156] The GI Bill was crafted principally as a reintegration tool for veterans but also considered to be a benefit that veterans earned through service and sacrifice.[157] As such, the GI Bill leaves the choice of educational attainment largely in the hands of veterans.[158]

The TAA program, in contrast to the GI Bill, requires displaced workers who are certified to participate in the program to be enrolled in eligible training programs to receive benefits.[159] While enrolled in a training program, beneficiaries can simultaneously receive unemployment compensation but once that it is exhausted, the Trade Readjustment Allowance (TRA), under the TAA, kicks in to replace unemployment benefits up to a combined 130 weeks.[160] A critical limiting factor on this particular statutory regime is that workers must have been displaced due to international trade deals.[161] As such, of the 4.8 million workers eligible for this program since 1974, only 2.2 million have received benefits.[162] This represents a miniscule average of only 50,000 workers per year from 1976–2018 who have actually received assistance through the program.[163] However, the TAA’s focus on education, retraining, and, in the case of older workers, wage replacement to offset decreased wages in new employment, could serve as a model for an economy-wide education benefits program.[164]

In a robot-centric productivity system, the United States can ill-afford to squander limited resources financing citizens’ educational goals if such goals do not meet workforce needs. In contrast to the GI Bill but in line with the TAA, a statutory solution to address AI disruption to the workforce should incorporate guidelines for what education and skills out-of-work employees should attain to maximize productivity and value in a new economy.[165] Based on the unknowability of future work needs, the cycle for determining what skills will be required in the future and then creating educational programs to meet them will likely be short.[166] As such, the government’s guidelines will likely require periodic and frequent adjustment necessitating shifts in the educational goals of out-of-work employees in order to meet national priorities.[167] The government should only subsidize the educational goals of out-of-work employees if the purpose of such education is to rejoin the workforce with useful and value-added skills.[168] That is, if radiology is largely conducted by robots powered by AI, then a person’s interest in a radiology education alone would likely not be optimal for the government to finance.[169]

The current student loan structure backed by the federal government does not force hard choices on borrowers.[170] The proposal that the government should become an arbiter of educational assets may leave the impression that a person will not be able to fulfill his or her educational ambitions if those ambitions do not correspond to a recognized workforce need. Unfortunately, this may largely be true.[171] But, private financing of one’s educational goals will likely always be available.[172] For the public interest, public finances should only be used to ensure maximum benefit to society,[173] which necessarily means that skills that are not useful in a future work setting should be deprioritized for the public good. The TAA could serve as a model due to its focus on reorienting displaced workers back into jobs.

Because the GI Bill’s focus is on education as a tool of reintegration for veterans, a statutory solution that more broadly addresses the disruption of AI to the workforce would likely make the GI Bill, with its primary focus on educational benefits, obsolete. Some states are already experimenting with free tuition at state-supported schools, which makes the primary educational benefit of the GI Bill superfluous.[174] The education system must necessarily be restructured in large measure to address a constant transition of people with outdated or outmoded skills to new and needed skills.[175] The whole workforce, including veterans, must be eligible. Educational benefits in the GI Bill will not be necessary in that world or will have to be substantially altered to be of value to veterans.[176]

The GI Bill has virtually no provisions for a payback of benefits, except in cases of fraudulent activity or when a veteran receives a “nonpunitive grade.”[177] Both the TAA and unemployment insurance largely follow the same principle: repayable in cases of fraud.[178] A contribution is not required in any of the statutes. However, veterans arguably contribute to their educational benefits in the corporal realm: their lives.[179] To be eligible for GI Bill benefits, servicemembers must serve in an active duty status, which could potentially put them in harm’s way.[180] Under a national educational program, an individual contribution could offset the costs borne directly by the government and indirectly by taxpayers, may help further the individual’s commitment to “payback” the government for its investment by serving a societal need for a period of time, and improve civic engagement.[181] Scholarships and loan repayments through federal work-study programs, Teach for America, and AmeriCorps are good examples of this concept.[182]

Under the FUTA, and similar state laws, employers bear the burden for supporting future unemployed persons, with the states and federal government serving as a temporary backstop during economic downturns.[183] Lawmakers should consider educational benefits as investments in the citizenry and, like with every investment, there should be an expectation of a return. In this case, the “return” is more people rejoining the workforce, thus paying taxes and contributing to the economy.[184] But, the statutory scheme may need to consider requiring applicants to repay a portion of their educational investment in the form of periodic payments if a community or national service obligation is impossible. Another possibility is that workers could be required to contribute to their own future educational needs through an investment vehicle such as an IRA or 401(k) drawn on employees’ paychecks, but with a similar effect of a 529 plan.[185] Some states already offer incentives for employer matching of employee 529 plans.[186] Perhaps a benefit afforded strictly to veterans could be a waiver of repayment or prepayment of their educational benefits under a universal education program.

The GI Bill, which has been incredibly influential in the educational hopes of the community of veterans, could be a similar starting point for a statutory scheme that encompasses all of the workforce.[187] Some elements of the GI Bill and the TAA, especially their focus toward education and training, could be roughly adapted, with modification, to meet the needs of a workforce disrupted by the impact of AI. Attainment of new skills and education will be crucial for displaced workers to reenter working society and return to being productive members of the economy.[188] Even basic courses that refresh displaced workers on minimal skills necessary to operate in modern workplaces would be beneficial.[189] The government has a major role to play in ensuring optimum employment.[190] The GI Bill and TAA could serve as models for new legislation that supports displaced workers by incentivizing education and skills acquisition in exchange for temporary benefits.

Creativity and ingenuity are often the products of small business.[191] Such attributes will be necessary to compete with automation and AI.[192] Interestingly, the original GI Bill provided funding for loans to small businesses started by veterans, but that provision was not renewed in subsequent amendments.[193] Now, the Small Business Administration (SBA) has made small business a focal point for reintegrating service members into society and ensuring former military members take advantage of financial benefits.[194] The SBA’s loan guarantee program provides qualified veterans with access to low-interest loans to pay for small business ventures.[195] The SBA does not provide the loan.[196] Instead, the SBA essentially acts as a guarantor to private lenders who in turn lend the money to the veteran for the business venture.[197]

Something similar to the SBA’s guarantee to veterans should be considered to encourage entrepreneurialism. A statutory solution should incentivize individual efforts to engage in new business ventures and diversify the overall government strategy of returning out-of-work individuals displaced by AI back into productive members of society.[198] Instead of attending school, an out-of-work employee could endeavor on a new business venture as a means of productively contributing to the economy.[199] Should someone wish to do so, the government could act as a guarantor, much as it does currently for small businesses, to facilitate low-interest loans that finance such ventures.[200]

The U.S. government generally does not finance new startup ventures.[201] But, in times of great economic upheaval or consequential moments in our past, the government has stepped in to guarantee certain critical economic activities for the benefit of the whole society.[202] Small businesses are the lifeblood of the U.S. economy.[203] Economic segments most likely to be hardest hit by the AI disruption include accommodations and food service, manufacturing, transportation, and retail.[204] Besides accommodations and food service, the remaining industries most likely to be disrupted consist of activities that employ large numbers of people.[205] Investing in small businesses and new ventures enhances domestic policies that boost employment.[206] Small business must be part of the solution.

The SBA’s spearheading of loan guarantees to small businesses has helped disadvantaged individuals gain access to credit that otherwise would not be available.[207] In a statutory solution to the upcoming AI disruption to the workforce, strong consideration should be made to loosen restrictions on access to credit for out-of-work individuals to endeavor on new business ventures (and create jobs).[208] Undoubtably, some will fail (and cost taxpayers) while some will succeed. Private lenders have little incentive to loan money to out-of-work individuals but those are the individuals who will need it most to start a new business.[209] The government must play a role in connecting people with business ideas to entities with money to finance them.

Educational and business efforts will fall flat if the fundamental needs of citizens are not met. According to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, physiological needs form the base of a self-actualization pyramid.[210] Without being able to satisfy a person’s need for shelter, food, clothing, and other basic survival needs, that person is unable to move into higher levels of the pyramid, including safety, love and emotional support, self and social esteem, and, finally, to self-actualization—the point where humans are capable of seeing optimal growth in personal satisfaction and productivity.[211] Although Maslow’s theory is not without criticism, it points to a fundamental fact that people must be able to care for basic needs before they are capable of taking on higher level tasks.[212] The GI Bill, and subsequent amendments, foresaw the need to ensure that basic needs were met coinciding with educational needs.[213] As part of the model for a statutory solution to the upcoming workforce disruption, the GI Bill provides a solid footing to tackle housing and subsistence needs for transitioning workers.

The GI Bill provides eligible veterans enrolled in accredited educational programs a monthly housing allowance tied to the average cost of living for an E-5 with dependents.[214] An E-5 is the fifth enlisted rank above the lowest rank, E-1.[215] In the Army, for example, an E-5 is a Sergeant.[216] The rate is then tied to the average living cost associated with the zip code where the educational institution is located.[217] For every month that the veteran is in an accredited educational program, the veteran receives a housing benefit prorated to the number of days in the month that he or she is actively enrolled.[218] For example, in a typical academic cycle for an undergraduate institution, the veteran is often fully enrolled for the month of September resulting in 100% payment of the allowed housing benefit, but only enrolled for 50% or less of the month of December. Consequently, the veteran’s housing allowance is only paid out at 50% for December.[219] This proration can lead to hardships for the veteran on occasion, but generally helps to allay living expense fears while the veteran is enrolled full-time in an educational pursuit.[220]

A statutory response to the upcoming AI disruption to the workforce should necessarily focus primarily on reorienting out-of-work individuals back into productive work by learning new skills. While the individual is learning new skills, especially if enrolled in a full-time program, there is little available time to take on other work to garner income and pay the costs of living.[221] Therefore, if an education-focused regime is envisioned as a solution, a corollary should be to address housing expenses, just as the GI Bill provides, for any individual enrolled in an accredited program. Veterans Affairs calculations based on zip code could be a good start, but the Internal Revenue Service also computes housing expenses, including utility costs, by county, which could be useful to determining monthly allowances for participants.[222]

A minimum basic income should be included into a comprehensive statutory solution to ease disruption caused by mass adoption of AI-empowered robotics. Provisions in the GI Bill definitively address minimal housing needs, which, as noted above, directly satisfy one the physiological elements at the base of Maslow’s Hierarchy.[223] However, the other elements—food, clothing, and other basic survival needs—are not addressed specifically in the GI Bill.[224] Because GI Bill housing benefits are structured to pay out according to the average housing cost for a given zip code, veterans are incentivized to acquire housing below that rate and allocate the difference to satisfying other basic needs. Unemployment insurance, on the other hand, does not directly take into consideration the cost of living but simply attempts to provide a portion of a worker’s lost income—roughly half—due to the loss of a job.[225] This, in a way, is an attempt to provide a minimal basic income to a worker displaced by a job loss, albeit typically at a much lower rate than benefits granted under the GI Bill just for housing.[226] The TAA program provides basic income to displaced workers who meet certification criteria but only after their unemployment insurance is exhausted, in most situations, and only if they are enrolled in eligible training programs.[227] All of these federal regimes envision some form of basic income, albeit indirectly as in the case of the GI Bill, to assist individuals transitioning from one job or kind of employment to another.

To ease the overwhelming burden off displaced workers, who very likely will require assistance to satisfy their basic physiological needs under Maslow’s Hierarchy, a minimum basic income should be granted based on reasonable eligibility criteria, such as enrollment in a certified training or educational program or operating a qualified small business.[228] This proposal differs from the concept of a basic income guarantee or a universal basic income. Proposals for a universal basic income, popularized lately in progressive circles but becoming more mainstream as a result of the Global Pandemic, generally have no eligibility criteria and would be payable to all citizens every month.[229] This idea is not new and in fact originates in conservative and libertarian thought in the 1970s.[230] Originally proposed as a way for wealthy nations to free up the individual from traditional support systems and allow a more open and mobile society,[231] the concept could be applied to a fully automated society where no humans worked any longer.[232] However, a universal basic income may be premature at present.[233]

The economy will need human labor for the foreseeable future but the threat from a universal basic income is that people may be disincentivized to work.[234] The objective for a minimal basic income, therefore, is to provide “enough to get by, but not enough to be especially comfortable” as a motivation for individuals to be as productive as possible.[235] The principal balance then is financial stability provided by the government in exchange for the individual seeking higher skills (that would be necessary to meet workplace needs in the future) or contributing to society via economic activity such as operating a small business.[236] The TAA program provides a model for administering benefits that, when combined with the educational focus of the GI Bill and the basic-needs focus of unemployment insurance, could serve as a solid foundation for a federal statutory solution to address mass disruption to the workforce.

Although the purpose of this note is to analyze possible statutory schemes that will enable the workforce to more effectively transition the disruption caused by mass adoption of AI and robotics, statutory solutions do not run themselves. An administrative bureaucracy will be necessary to implement and oversee the structural changes to our educational and workforce system. The burden of administering veterans’ benefits falls to the Veteran’s Benefits Administration under the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.[237] The Department of Labor (DOL) oversees the TAA program and unemployment insurance through a network of collaborative programs at the state level.[238] Further, the Department of Education (DOE), so far absent from discussion, provides federal oversight of loan administration to borrowers seeking higher education, among other prerogatives.[239] It may be time to combine the DOL with the DOE to create a new consolidated agency with administrative oversight of both the workforce and educational system.[240] Although the Trump administration proposed the creation of the Department of Education and the Workforce in 2018, there are serious concerns that the DOE’s traditional role as enforcer of civil rights may be usurped in such a merger.[241] Education in the liberal arts, a subject likely to be unnecessary to serve workforce needs, also serves the needs of democracy, even if it does not lead to a job required by industry.[242] Such concerns may be the reason why Congress has yet to act on the proposal. Assuming that civil rights concerns can be addressed and resolved, a merger along the Trump administration’s proposal may make sense to assist with educational alignment that best meets workforce needs in a future where we as yet do not know what those needs will be.[243]

Combining the mandates of both the departments of Labor and Education will allow for synergies in policy with resultant cost savings that should lead to outcomes favorable to workforce competitivity on the international scale.[244] Further, elements of the Veterans Benefits Administration that oversee educational benefits could be eliminated or the expertise transferred to the newly consolidated agency since educational benefits will be available to all citizens transitioning from one job to another, not just veterans. Intellectual safeguards for our democracy can be implemented through solutions such as mandating that training programs and educational concentrations funded by the federal government incorporate liberal arts studies to enlighten beneficiaries on topics necessary to keep our system of government and society healthy.[245]

The promotion and enforcement of civil rights and equal access to education should continue as a mandate for a consolidated entity. Both departments currently have inspectors general to review the efficacy of the respective department’s programs and policies.[246] A consolidated agency’s inspector general could create a subordinate, stand-alone investigative office to specifically review agency decisions for compliance with civil rights laws. Additionally, or alternatively, the current Office for Civil Rights under the DOE could continue under a consolidated entity with an expanded mandate to enforce civil rights law in both labor and education policies and programs.[247] Unfortunately, neither of these two possibilities are included for consideration in the Trump proposal.[248]

The time is right to consolidate the Departments of Labor and Education and to empower that entity to oversee the implementation of a federal regime that protects the workforce from the inevitable disruption caused by automation and simultaneously orients labor through education to meet the needs of the future economy. Considerations for equitable access to educational benefits and vigorous enforcement of civil rights laws must be incorporated into this mandate. Congress is best positioned to evaluate these concerns and implement proper safeguards into a statutory solution.

To apply a benefits regime based on the GI Bill, the TAA, and Unemployment Insurance programs to the entire workforce will require substantial funding. Unemployment compensation payments in 2010 alone accounted for $150 billion in federal and state government expenditures.[249] Unemployment then only rose to ten percent at its peak.[250] Although much more analysis would be needed to determine approximate costs, if simply using unemployment insurance expenditures as a starting point, a thirty-percent-unemployment rate would necessitate roughly three times the expenditures, at a minimum, not accounting for inflation or other costs. Unemployment insurance expenditures under a thirty percent unemployment scenario would be at least $450 billion, per year, at present rates. Because unemployment compensation is a stopgap measure not intended to be used to help pursue the attainment of new skills, the cost associated with reorienting the unemployed to new skills or other modes of productive employ must necessarily be substantially higher than $450 billion.[251]

The costs of absorbing a huge proportion of the workforce whose skills are made obsolete by automation must be borne by someone.[252] Businesses, as the primary beneficiaries of the benefits of AI, should pay the largest chunk of the tab.[253] The power of AI to automate routine tasks and make sense of massive amounts of information provides an exceptional incentive for businesses to adopt such cost-saving and profit-maximizing tools. Therein lies the consequential space where government can capitalize on such profits for the benefit of the workforce in general.[254] This paper does not propose to know where in this space a company would determine that adopting AI and replacing currently human-centric tasks would be more profitable; businesses should be taxed up to the point where a company would decide that such replacement would be optimal. The current tax structure levies a considerable burden on labor-intensive industries.[255] Taxing entities based on their capital, rather than their payroll, would shift the burden to those entities that have traditionally been allowed to free-ride on their obligation to contribute to social safety nets, such as social security or programs for the elderly.[256]

Much ado has been made of the Trump administration’s tax cuts, especially for business, and their intended effects on income growth and distribution across the economy.[257] The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 established a new corporate tax rate of twenty-one percent, below other Western industrialized nations.[258] Although the economic effects are still being debated, businesses are wholly unlikely to ever clamor for an increase in the tax rate.[259] But an increase will likely be necessary to pay for a robust statutory solution modeled on the GI Bill, the TAA, and the FUTA that encompasses broad protections and safeguards for employees; however, the tax rate should be individualized to the business and its particular adoption of automation.[260] The higher the ratio of capital investment in automation compared to labor, the higher the tax rate that should be assessed. This individualization of tax rates could be possible with updates to the tax code and reporting mechanisms—no small feat and also beyond the scope of this note. AI, in fact, could make tax individualization more effective.[261]

We do not know for certain what employment will look like in a future dominated by AI. With varying degrees of confidence, theorists, scientists, and AI experts have proposed wide-ranging predictions concerning the number of jobs that will ultimately fall to robots. Using a rough estimate that in the next fifteen years thirty-to-forty percent of the workforce will lose their current jobs due to AI automation, there is a profound need to prepare our society and economy for that likely eventuality. Frankly, no one can accurately predict the amount of disruption that will occur. There is a potential crisis on the horizon and some of its effects are already present. Just like the government responded to massive workforce disruption in the Great Depression by enacting reforms meant to provide some protection to employees, such as unemployment compensation and labor security, Congress must act now to avert a similar disruption when AI automates millions of jobs. Taking another New Deal era act, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, or GI Bill, together with the Trade Adjustment Assistance Program and elements of the unemployment insurance program, Congress should enact a robust and visionary statute for all citizens that guarantees educational and employment support in the transition to the next phase of our economy.

- * J.D. Candidate, University of Colorado, Class of 2021; MBA, University of Texas at Austin, Class of 2016; B.A., Texas Christian University, Class of 2005. My sincere thanks to the staff, students, and advisors on the CTLJ for their thoughtful and considerate feedback on this Note. ↑

- . Artificial Intelligence, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/artificial%20intelligence [https://perma.cc/E43Q-J3MP] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). ↑

- . Susan Fourtané, The Three Types of Artificial Intelligence: Understanding AI, Interesting Engineering (Aug. 25, 2019), https://interestingengineering.com/the-three-types-of-artificial-intelligence-understanding-ai [https://perma.cc/79DT-KH7S]; David T. Laton, Manhattan_Project.exe: A Nuclear Option for the Digital Age, 25 Cath. U. J. L. & Tech. 94 (2017). ↑

- . Fourtané, supra note 2. ↑

- . See Aman Goel, How Does Siri Work? The Science Behind Siri, Magoosh: Data Science Blog (Feb. 2, 2018), https://magoosh.com/data-science/siri-work-science-behind-siri/ [https://perma.cc/5JZX-P93L]. ↑

- . Tanyaa Jajal, Distinguishing between Narrow AI, General AI and Super AI, Medium (May 21, 2018), https://medium.com/@tjajal/distinguishing-between-narrow-ai-general-ai-and-super-ai-a4bc44172e22 [https://perma.cc/6PZX-AQEZ]. ↑

- . John Loeffler, Should We Fear Artificial Superintelligence, Interesting Engineering (Feb. 23, 2019), https://interestingengineering.com/should-we-fear-artificial-superintelligence [https://perma.cc/X922-4EN4]. ↑

- . See Leo Rogers, Artificial Super Intelligence: Upgrade in Technology or the Downfall of Humanity?, Indus. Heating (Sept. 1, 2017), https://www.industrialheating.com/articles/93719-artificial-super-intelligence-upgrade-in-technology-or-the-downfall-of-humanity [https://perma.cc/HVQ7-7VCV] (discussing broad potential risks if computers are programmed to make decisions instead of humans). ↑

- . Katerina Pouspourika, The Four Industrial Revolutions, Inst. of Entrepreneurship Dev. (June 30, 2019), https://ied.eu/project-updates/the-4-industrial-revolutions/ [https://perma.cc/3NTN-R42T]. ↑

- . See Artemis Manolopoulou, The Industrial Revolution and the Changing Face of Britain, British Museum, https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/publications/online_research_catalogues/paper_money/paper_money_of_england__wales/the_industrial_revolution.aspx [https://perma.cc/FX4H-KMKG] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See generally R. Austin Freeman, Some Ethical Consequences of the Industrial Revolution, 33 Int’l. J. of Ethics 347 (1923) (arguing that increased efficiency and profitability leads to an unethical tradeoff for craftsmen and consumers). ↑

- . Kashyap Vyas, How the First and Second Industrial Revolutions Changed Our World, Interesting Engineering (Mar. 12, 2018), https://interestingengineering.com/how-the-first-and-second-industrial-revolutions-changed-our-world [https://perma.cc/43PJ-4CDZ]; Interchangeable Parts Manufacturing in the Industrial Revolution, Hist. Crunch Writers (Aug. 15, 2019), https://www.historycrunch.com/interchangeable-parts-manufacturing-in-the-industrial-revolution.html#/ [https://perma.cc/QA5B-W98B]. ↑

- . See America’s Gilded Age: Robber Barons and Captains of Industry, Maryville U., https://online.maryville.edu/business-degrees/americas-gilded-age/ [https://perma.cc/2DP5-MB89] (last visited Oct.18, 2020). ↑

- . The Industrial Revolution: Powering the Future with Data, Controtek Solutions (Jan. 21, 2019), https://controtek.com/the-industrial-revolution/ [https://perma.cc/KF8S-7KVA]. ↑

- . See Klaus Schwab, The Fourth Industrial Revolution: what it means, how to respond, World Econ. F. (Jan. 14, 2016), https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/ [https://perma.cc/AL3Z-NZGT]; see generally Klaus Schwab, The Fourth Industrial Revolution (Crown Publ’g Grp. ed., 2017). ↑

- . See Anthony Knowles, II, Automation, Work, and Ideology: The Next Industrial Revolution and the Transformation of “Labor,” (Dec. 2017) (unpublished master’s thesis, Univ. of Tenn. at Knoxville), https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6214&context=utk_gradthes [https://perma.cc/65MD-PQYZ]. ↑

- . Id. at 3. ↑

- . Charles Post, Plantation Slavery and Economic Development in the Antebellum Southern United States, 3 J. Agrarian Change 289, 292–93, 325–26 (July 2003); Ralph A. Austern, Monsters of Protocolonial Economic Enterprise: East India Companies and Slave Plantations, 4 U. Chi. Critical Hist. Stud. 139, 141-42, 159 (2017). ↑

- . See Industrialization, Labor, and Life, Nat’l Geographic (Jan. 27, 2020), https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/industrialization-labor-and-life/7th-grade/ [https://perma.cc/7KFP-V5QU] (describing the trend of farmers in Great Britain migrating from rural communities to urban areas in search of work during the Industrial Revolution). ↑

- . Sushil Khanna, Capital and Finance in the Industrial Revolution: Lessons for the Third World, 13 Econ. & Pol. Wkly. 1889, 1890 (1978) (discussing the modest accumulation of capital prior to 1800 and the growth of fixed capital investment relating to the growth of factories in Great Britain). ↑

- . Robert Allen, Capital Accumulation, Technological Change, and the Distribution of Income During the British Industrial Revolution, Oxford Dept. Econ., June 2005, at 5. ↑

- . See David B. Audretsch, Org. for Econ. Co-operation & Dev., What Works in Innovation Policy? New Insights for Regions and Cities: Developing Strategies for Industrial Transition 22–24 (2018) (discussing that the three prior industrial revolutions resulted in transitions of the workforce through automation of routine tasks while predicting that the coming fourth industrial revolution will result in a massive transition as technology and capital replace non-routine tasks). ↑

- . Martin Ford, Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future 240 (2016). ↑

- . Audretsch, supra note 22, at 6. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id. at 8. ↑

- . See id. at 22. ↑

- . Ford, supra note 23, at 223 (“jobs comprising about 47 percent of total US employment—roughly 64 million jobs—have the potential to be automated within ‘perhaps a decade or two’”). ↑

- . See Byron Reese, AI Will Create Millions More Jobs Than It Will Destroy. Here’s How, Singularity Hub (Jan. 1, 2019), https://singularityhub.com/2019/01/01/ai-will-create-millions-more-jobs-than-it-will-destroy-heres-how/ [https://perma.cc/7S6X-5YLS]. ↑

- . See James Manyika et al., A Future That Works: Automation, Employment, and Productivity, McKinsey Global Inst., 2017, at 10–11 [hereinafter Manyika et al., A Future That Works]. ↑

- . Elena Holodny, 19 Robber Barons Who Built and Ruled America, Bus. Insider (July 29, 2017), https://www.businessinsider.com/robber-barons-who-built-and-ruled-america-2017-7 [https://perma.cc/WJ8L-BUX8]. ↑

- . See id. ↑

- . Mordecai Kurz, On the Formation of Capital and Wealth: IT, Monopoly Power and Rising Inequality 21–22,Stan. U. Dep’t of Econ., Working Paper No. 17-016, (June 25, 2017), https://web.stanford.edu/~mordecai/OnLinePdf/Formation%20of%20Capital%20and%20Wealth%20Draft%209%2010%202017.pdf [https://perma.cc/N47J-JSVH]. ↑

- . Anton Korinek & Joseph E. Stiglitz, Artificial Intelligence and its Implications for Income Distribution and Unemployment 1–2 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 24174, 2017), https://www.nber.org/papers/w24174.pdf [https://perma.cc/5YJG-YMNK]. ↑

- . Author’s visual depiction of types of work that will likely be automated in the near future. See Darrell M. West, The Future of Work: Robots, AI, and Automation 68–71 (2018). ↑

- . Milan Markovic, Rise of the Robot Lawyers, 61 Ariz. L. Rev. 325, 326 (2019). ↑

- . Harold Stark, Prepare Yourself, Robots Will Soon Replace Doctors in Healthcare, Forbes (July 10, 2017), https://www.forbes.com/sites/haroldstark/2017/07/10/prepare-yourselves-robots-will-soon-replace-doctors-in-healthcare/#7cd4da4e52b5 [https://perma.cc/6EHB-M8TA]. ↑

- . See generally Kurt Vonnegut, Player Piano (1952) (exploring a future where machines do all work for the benefit of a few elites while the rest of the population struggles with purpose and rebels). ↑

- . Ford, supra note 23, at 229–30. ↑

- . See Samantha Marcus, N.J. becomes first state to mandate severance for Workers if they are part of a mass layoff, NJ.com (Jan. 21, 2020), https://www.nj.com/politics/2020/01/nj-becomes-first-state-to-mandate-severance-for-workers-if-they-are-part-of-a-mass-layoff.html [https://perma.cc/ZN45-JAYT]. ↑

- . See generally Amy Goldstein, Janesville: An American Story 1 (2017) (describing the efforts of community members in Janesville, Wisconsin, to alleviate the social and economic disruption caused by the closure of a GM factory). ↑

- . See Edwin E. Witte, Development of Unemployment Compensation, 55 Yale L.J. 21 (1945) (Arguing that unemployment compensation is insufficient in an economic crisis)a ↑

- . Id. at 22. ↑

- . See Chad Stone & William Chen, Introduction to Unemployment Insurance, Ctr. on Budget & Pol. Priorities (last updated Mar. 24, 2020), https://www.cbpp.org/research/introduction-to-unemployment-insurance [https://perma.cc/K7B3-B8RV]. ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See id. ↑

- . See Unemployment Insurance Fact Sheet, U.S. Dep’t Lab., https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/factsheet/UI_Program_FactSheet.pdf [https://perma.cc/TGP8-PXTV] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). ↑

- . See Witte, supra note 42. ↑

- . See Kimberly Amadeo & Somer G. Anderson, Unemployment Rate by Year Since 1929 Compared to Inflation and GDP, The Balance (Sept. 17, 2020), https://www.thebalance.com/unemployment-rate-by-year-3305506 [https://perma.cc/4QH7-6C3D]. ↑

- . See Burton W. Folsom, What Ended the Great Depression?, Found. for Econ. Educ. (Feb. 24, 2010), https://fee.org/articles/what-ended-the-great-depression/ [https://perma.cc/VBD7-9R6S] (asserting that the massive mobilization of millions of people, coupled by the government’s assumption of equally massive amounts of debt, to fight in the war ended the Great Depression). ↑

- . See Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey (graph) in Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject, U.S. Bureau of Lab. Stat., https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000 [https://perma.cc/RTW6-TEJ6] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . Id.; see also Heather Long & Andrew Van Dam, U.S. unemployment rate soars to 14.7 percent, the worst since the Depression era, Wash. Post (May 8, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/05/08/april-2020-jobs-report/ [https://perma.cc/324B-PWD4]. ↑

- . Coronavirus, World Health Org., https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 [https://perma.cc/SY4F-VZZS] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). ↑

- . See Jay Shambaugh, The Economic Policy Response to COVID-19: What Comes Next?, Brookings (Mar. 16, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/03/16/the-economic-policy-response-to-covid-19-what-comes-next/ [https://perma.cc/F6PR-RCYU]. ↑

- . Gary Burtless, Unemployment Insurance for the Great Recession, Brookings (Sept. 15, 2009), https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/unemployment-insurance-for-the-great-recession/ [https://perma.cc/CP3V-5TTF] (“When unemployment is high and job finding is hard, many UI claimants exhaust their regular benefits. In the worst month following the 1981-82 recession, 41% of UI claimants exhausted their regular state UI benefits.”). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See Paul Davidson, What Do Jobless Do When Unemployment Checks Run Out?, CNBC (Aug. 3, 2012), https://www.cnbc.com/id/48484737 [https://perma.cc/86CR-BPR2]; see also Why We Need to Continue Unemployment Insurance Benefits, Ctr. for Am. Progress (Nov. 15, 2020), https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2010/11/15/8616/why-we-need-to-continue-unemployment-insurance-benefits/ [https://perma.cc/LXR6-T94S] (showing that 3.3 million families were kept out of poverty in 2009 due to unemployment compensation). ↑

- . See Ann Huff Stevens, Transitions Into & Out of Poverty in the United States, U.C. Davis Ctr. for Poverty Res., https://poverty.ucdavis.edu/policy-brief/transitions-out-poverty-united-states [https://perma.cc/VK6S-FM2S] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“The exit rate from poverty is 56 percent after just one year poor but falls to 13 percent after seven or more years in poverty.”). ↑

- . See Teresa A. Sullivan et al., The Fragile Middle Class: Americans in Debt (2000); but see Todd J. Zywicki, An Economic Analysis of the Consumer Bankruptcy Crisis, 99 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1463, 1505 (2005) (arguing that economic data does not support a positive correlation between unemployment and bankruptcy rates). ↑

- . See Just the Facts: Consumer Bankruptcy Filings, 2006–2017, U.S. Courts (Mar. 7, 2018), https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2018/03/07/just-facts-consumer-bankruptcy-filings-2006-2017 [https://perma.cc/475V-4D2M]. ↑

- . See id. ↑

- . See Amadeo & Anderson, supra note 49. ↑

- . See Sebahattin Demirkan, Harlan Platt & Majorie Platt, Does Unemployment Steer Personal and Corporate Bankruptcies?, 9 Rev. Bus. & Econ. (forthcoming), http://ssrn.com/abstract=1524484 [https://perma.cc/QFW8-6GXJ]. ↑

- . Sullivan et al., supra note 60, at 15. ↑

- . Demirkan et al., supra note 64, at 25. ↑

- . Erin Duffin, Personal bankruptcy rate in the United States as of September 2019, by state, Statista (Jan.2, 2020), https://www.statista.com/statistics/303570/us-personal-bankruptcy-rate/ [https://perma.cc/9NBQ-YGX2]. ↑

- . QuickFacts: Population, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219 [https://perma.cc/UAM3-RHEA] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). ↑

- . See Stacy Lastoe, A Newly Unemployed Person’s Guide to Severance Pay, The Muse, https://www.themuse.com/advice/a-newly-unemployed-persons-guide-to-severance-pay [https://perma.cc/DGY2-MB5J] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (noting that the typical worker might get severance for no other reason than if an employer fails to abide by the WARN Act). ↑

- . Severance Pay, U.S. Dep’t Labor, https://www.dol.gov/general/topic/wages/severancepay [https://perma.cc/B8SP-JKWF] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020). ↑

- . See Alison Doyle, What to Expect in a Severance Package, The Balance (July 21, 2020) https://www.thebalancecareers.com/what-to-expect-in-a-severance-package-2063385 [https://perma.cc/V5CE-DF5N] (last updated July 21, 2020) (if severance payments are not specified in the current collective bargaining agreement, a company is under no obligation to provide severance benefits to employees represented by a labor union); Neil Kokemuller, Why Do Companies Give Severance Packages?, Chron, https://smallbusiness.chron.com/companies-give-severance-packages-70373.html [https://perma.cc/9Q7N-D4HG] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“[B]usiness owners often feel a sense of fairness or responsibility when offering severance.”). ↑

- . See Doyle, supra note 71. ↑

- . See Kokemuller, supra note 71 (proposing that businesses adopt severance in exchange for terminated employees promising not to sue under a discrimination or wrongful termination claim). ↑

- . See Q&A–Understanding Waivers of Discrimination Claims in Employee Severance Agreement, U.S. Equal Emp. Opportunity Comm’n, https://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/qanda_severance-agreements.html [https://perma.cc/68GD-KVU5] (last visited Oct. 18, 2020) (“A waiver in a severance agreement generally is valid when an employee knowingly and voluntarily consents to the waiver.”). ↑

- . Id. ↑

- . See Susan M. Heathfield, Why An Employer Might Want to Provide Severance Pay, The Balance (May 28, 2020), https://www.thebalancecareers.com/severance-pay-1918252 [https://perma.cc/4HA9-KQRF] (arguing that former employees may be motivated to negotiate for more than standard salary and benefits as provided for in a proposed severance or employment agreement). ↑

- . See id. (suggesting that obtaining the employee waiver is the goal for the employer in a severance agreement). ↑

- . Marcus, supra note 40. ↑

- . Vanessa Romo, New Jersey Mandates Severance Pay for Workers Facing Mass Layoffs, NPR (Jan. 22, 2020), https://www.npr.org/2020/01/22/798727332/new-jersey-mandates-severance-pay-for-workers-facing-mass-layoffs [https://perma.cc/7GVL-EPEG]. ↑