Systems Theory, Surveillance Capitalism, and Law: Native Wisdom and Feedback Loops to Boost the Constructive Use of Big Data

Adam J. Sulkowski, Danielle Blanch-Hartigan, Caren Beth Goldberg, Amy K. Verbos, Maoliang Bu, and Remy Michael Balarezo Nuñez[1]†

Print Version: Native Wisdom & Big Data

I. Data Collection-and-Use: Evolution and Application 137

A. Surveillance Capitalism 137

B. Abuses of Our Online Presence in the Context of Employment 138

C. The Implications of Expanded Data Collection-and-Use in Healthcare 140

II. A Cautiously Offered Counter-Narrative: Why Pervasive Data Collection Can Be Good 143

A. Models for Success for More Regulation by Disclosure 144

1. Mandatory Financial Disclosures 145

2. Toxic Release Inventory 145

3. Sustainability Reporting can Improve Business Function 147

B. A Holistic Approach is Instructive 148

IV. Implications for Legal Counsel and Policymakers 157

This is the first work of legal scholarship to offer a new feedback loop model derived from systems-thinking literature and Native wisdom traditions. It applies these conceptual frameworks to a discussion about how attorneys, their corporate clients, and public policymakers can form and execute a pragmatic approach to regulating data collection and usage, through either voluntary self-regulation or using the tools of government.

“The Age of Surveillance Capitalism,” by Shoshana Zuboff, is one of the loudest alarms concerning the pervasiveness of data collection by businesses and the comparatively lesser-known uses of that data for shocking purposes of human behavior prediction and manipulation.[2] This paper begins by reviewing some of the rich and rapidly growing legal scholarship related to surveillance capitalism. Next, the authors introduce their recent observations on the use of data by businesses. We then offer a hopeful counter-narrative: the deep integration of widespread data collection, if steered appropriately, can be a part of the solution to the widely acknowledged blind-spots of short-termism in capitalism, as practiced until the present moment at the dawn of the third decade of this millennium.[3] The authors offer a new model of feedback loops and apply it to this arena of legal scholarship alongside principles borrowed from Native wisdom traditions. This simple, yet profound model can help attorneys, their corporate clients, and public policymakers consider the collection and use of data in a way that advances long-term and holistic thinking, while curbing the all too familiar systemic risks.

The goal of this section is to provide background and context for our thesis and main points. We will first review the elements of surveillance capitalism. We will then examine how “surveillance capitalism” is specifically objectionable in two contexts: employment and health information.

Zuboff, who coined the phrase “surveillance capitalism” defines it as “the unilateral claiming of private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data.”[4] This behavioral data is valuable when packaged into a prediction product for those who can use such information (namely, advertisers) to predict consumer actions.[5] For example, knowing that individuals might resist such data collection if they are aware that their data is accumulated and translated into behavioral data, “at Google… [i]t was understood that these methods had to be undetectable.”[6] Whether such data collection and use could, in fact, be allowed to commence with little to no regulation, was the subject of much debate at the Federal Trade Commission.[7] According to Zuboff, in 1997, while technology executives pushed for self-regulation, civil libertarians warned of “an unprecedented threat to individual freedom” in the process where we risked people simply becoming “chattel for commerce.”[8] The federal government did not act then, and with few exceptions, data monitoring has essentially been unchecked and unregulated.[9]

Looking to 2021, we can clearly see the results of such a hands-off approach. It is not just Google, but Amazon, Facebook, and a whole array of applications that have gathered information on us. “Our lives have been colonized by Big Data—Google, of course, but also Facebook and Amazon and the myriad of apps, devices, and utilities they propagate.”[10] “We thought that we search Google, but now we understand that Google searches us. We assumed that we use social media to connect, but we learned that connection is how social media uses us.”[11] How this information is used varies by context. For example, in some situations, such as decisions of whether to employ someone, legal constraints may prohibit the use of certain characteristics such as gender and age.[12]

As organizations are increasingly reliant on technology in recruitment and selection, two phenomena have garnered particular attention. The first, social media assessments (SMAs), refers to reviewing an applicant’s social media profiles and posts.[13] This practice has become increasingly common, with nearly two-thirds of recruiters conducting SMAs at least some of the time,[14] and over half of recruiters reviewing candidates’ Facebook profiles.[15] While this may seem like a reasonable practice at first glance, it raises legal and ethical concerns.

Recent research suggests job-irrelevant information on candidates’ Facebook profiles, such as political affiliation[16] and religion,[17] strongly influence assessments of candidates. Moreover, in both of these studies, job-relevant information such as candidates’ internships and grade point average (i.e., factors that seem they should matter) had no significant effects on employability ratings.[18] Adding to the problem, Van Iddenkinge, et al. showed that SMAs involving Facebook profiles are not predictive of performance, turnover intentions, or actual turnover.[19] Further, there are mean differences in SMA scores across race and gender, suggesting a potential for adverse discriminatory impacts that appear to violate the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[20]

The second area in human resources where data may be misused is in targeted recruitment advertisements. Just as data analytics have allowed advertisers to use targeted marketing with pinpoint precision, so too have recruiters been able to make use of this unprecedented accuracy in targeting audiences of potential applicants that use Google and Facebook.[21] The downside of such an approach is that it expressly excludes individuals, particularly those in certain demographic groups.[22] In their exposé on the subject, Larson, Varner, Tobin, and Angwin published a list of over three dozen companies that used age-restricted employment advertisements, including some well-respected employers such as Microsoft, Facebook, and Goldman Sachs.[23] At least one class-action lawsuit has already been filed challenging this practice. In Bradley v. T-Mobile U.S. Inc., plaintiffs argued that age-restricted employment advertisements constitute intentional discrimination in violation of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act and other local statutes.[24] The outcome of this case could set an important precedent that will influence whether employers continue to rely on targeted recruitment advertisements.

The growth of automated passive sensing, private health data collection, and artificial intelligence is set to revolutionize the way we practice medicine and public health. Artificial intelligence can aid oncologists in determining evidence-based, tailored treatment options.[25] Mobile sensing platforms passively collecting digital trace data can successfully predict post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression.[26] Automated healthcare technologies can help achieve “the triple aim” of healthcare improvement by lowering skyrocketing costs, improving quality of care, and increasing healthcare access.[27]

Automated technologies strive to augment human capability in predicting, screening, diagnosing, and treating disease. However, despite the enormous promise of these innovations, we must ensure that we integrate automated technologies into clinical care thoughtfully and carefully to avoid negative and unintended consequences. Namely, we must strive to implement data-driven solutions without putting patients at risk for privacy violations, and without sacrificing humanism in medicine.[28] Humanistic healthcare necessitates an ethical and patient-centered approach; it is healthcare that develops human connections to foster healing relationships, and that integrates patient values and perspectives to demonstrate respect.[29] It is imperative that research on the effective integration of automated technologies in clinical care incorporates representative data and cross-cultural perspectives, to avoid bias in algorithms and applications.[30]

In addition to automation in healthcare, the growth in the availability of health information has led to increased consumption of knowledge and attempts at self-diagnosis: 80% of US adults consult the internet for health information.[31] Yet, as health information becomes more decentralized and accessible, misinformation proliferates and recommendations are often not based on clinical best practices or scientific evidence.[32] Despite the promise of information-seeking, patient engagement for the democratization of care and shared decision-making, misinformation puts patients at risk.[33] Many patients do not discuss online information-seeking with professional providers.[34] The scope of this essay primarily concerns data collection-and-usage, rather than misinformation, but nonetheless, we shall briefly return to the challenge of misinformation in the final sections.

Electronic health records (EHRs) and patient portals, which allow patients to access their medical records, also have tremendous promise. The 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act mandated the accelerated implementation of electronic medical records for meaningful use.[35] However, there have been significant impacts on clinical interactions, which are now frequently mediated by a digital device.[36] Even if a patient and doctor are in the same room, patients increasingly feel distanced as providers’ backs are quite literally turned away, or they follow a line of questioning dictated by what pops up on a screen rather than the patients’ concerns.[37] Moreover, the incompatibility of EHR systems across providers and healthcare systems, as well as the digital divide limiting access to patient portals, means that potential benefits of highly coordinated care and reduced disparities in access are not fully realized.[38]

The next wave of healthcare technology is automation through artificial intelligence and data-driven diagnostics.[39] Like past advances, we will see in the following paragraphs how technology is outpacing the ability to study the ideal integration for maintaining humanistic care. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is working towards increased certification and regulation of digital health technologies through its Digital Health Innovation Action Plan.[40] Existing regulations and payment structures can also limit the implementation of effective approaches; for example, HIPAA can be both powerful protection for patient health information (PHI) and a legal barrier to implementation.[41] Clinical trials of new healthcare technologies assess intervention effectiveness or assess diagnostic accuracy, but often fail to assess the impact on the patient-provider relationship, or consider the broader implementation implications for privacy and security.[42]

Moreover, bias in artificial intelligence and machine learning models in healthcare may intensify health disparities.[43] Models built and tested using narrowly defined subgroups, or those not representative of vulnerable populations, may be inaccurate when applied more broadly.[44] Artificial intelligence can help identify disparities in care, but we must ensure that providers and organizations that serve vulnerable populations have equal uptake in these innovations.[45]

We must ensure that data-driven solutions in healthcare are equitably applied, protect personal health information, and enhance—rather than replace—the healing relationships between patients and providers.

While some may bemoan the reach of big tech, and abuses enabled by the obliteration of privacy, others point to the conveniences and societal benefits supported by these same platforms. Expanded access to information, navigation services, and instant free communication are three commonly cited examples.[46]

Here, we will build upon the idea that pervasive data collection could be used—under certain conditions—for the common good. To structure this argument, we will start by highlighting the successful use of transparency regimes as an effective regulatory tool—one that both industry players and critics have come to accept as obviously desirable.[47] We will also look to the context of Native or Aboriginal governance as instructive. As argued in other contexts, our tools and rules are parts of the problem, but a sine qua non to the solution is a more holistic and long-term mindset.[48]

Transparency systems are government-mandated rules which require entities to make information about things such as their products or practices publicly available.[49] In the US and abroad, government-implemented disclosure rules have helped to reduce financial and health risks.[50] “The rationale for government intervention starts with the premise that information asymmetries in market or political processes obstruct progress toward specific policy objectives.”[51] Experiences with respect to mandatory financial disclosures, the toxic release inventory, and environmental sustainability reporting, all point to the effectiveness of regulation by transparency, as will be examined in the following sections.

The 1933 Securities Act and 1934 Securities and Exchange Act ushered in a detailed financial disclosure and transparency system to protect investors.[52] This was accomplished by not only shedding light on potentially hidden risks for investors, but also by increasing the pressure on those in corporate governance whose conduct impacts the capital markets.[53] This system of financial reporting has been effective, and the information provided as a result of these mandatory disclosure rules has become an intrinsic part of the decision-making process for investors and companies.[54] Research supports the success of these measures in reducing risks[55] and enhancing governance.[56] Interestingly, researchers have discovered that improved governance also happens in foreign companies that adopt financial disclosure rules similar to those of the US.[57]

In the wake of the 1984 Bhopal, India tragedy, which was caused by a chemical accident at Union Carbide, Congress acted by requiring disclosure of certain toxic chemical information by companies that met minimum thresholds.[58] This law, known as the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) of 1986, requires manufacturers to annually disclose the quantity of toxic chemicals released into the environment and kept in communities, and was intended to encourage a reduction of such emissions.[59]

Initially, this law was met with little enthusiasm from the EPA, which viewed the disclosure rules as simply an additional burden for regulators.[60] However, theTRI requirement soon became viewed by regulators as one of the federal government’s most effective pollution-control measures: [61]“Many targeted companies, especially those with national reputations to protect, made commitments for long-term reduction of toxic releases in response to the first disclosures of shocking information and took some specific actions to minimize releases.”[62] Congress expanded the initial TRI reporting requirements with the passage of the Pollution Prevention Act, which added a requirement to report remedial or accidental toxic releases in addition to routine releases.[63] A review of the impact of the TRI indicated that those companies which were deemed to be high-intensity polluters experienced greater declines in stock value compared to those companies who fared better per disclosures.[64] Most importantly, this drop appears to have been an incentive for those companies to reduce release of substances included in the TRI, and had the added effect of making those companies less likely to be fined for violations of environmental laws.[65] The ongoing effectiveness of the TRI continues to depend on open access to accurately reported data that is freely available and can be used to spots trends and in turn exert influence on companies.[66]

There is ample evidence that business executives invest in sustainability reporting, which is the gathering and publishing of data on environmental, societal, and other impacts.[67] Businesses do this for a variety of reasons, including managing their reputations[68] and enhancing their financial performance,[69] share price, and returns to investors.[70] Investors seem to value such information enough that it is reasonable to ask if reporting on societal, environmental, and governance practices is an evolving legal expectation.[71] Indeed, S&P 500 companies reporting corporate social responsibility and sustainability increased from 20% in 2011 to 90% in 2019.[72]

Recently, advances in data sciences—specifically blockchain—have led to the realization that more transparency in the use of distributed online ledgers could improve sustainability performance.[73] Such advances could also allow for the automation of codes of ethics. For example, there is no reason that a company could not automate the commitment to offset all of its carbon emissions to be 100% carbon neutral.[74] Such enhanced transparency and automation of administrative decisions should lead managers and legal experts to proactively ponder contingencies and consequences.[75] In fact, the eagerness of some business leaders to become advocates for disruptive change,[76] coupled with the advances in data transparency and already fundamentally changed modes of interaction, such as gig economy employment, mean that it is overdue for legal thinkers to question and suggest reforms to the legal frameworks and relationships of today[77]

Traditional Native, Aboriginal and Indigenous ways of being bring a long-term and relational perspective to governance and ethical decision making for socially, environmentally and financially sustainable decisions.[78] The important qualitative difference between decisions made from a relational ethics perspective versus moral rationality perspective is that the former is based upon interdependence and an affective relationship pursuant to which humans are responsible to all things created,[79] while the latter does not have an affective or a spiritual component. As we will discuss in the following section, data systems and feedback loops can be constructed to enforce a holistic and relational mindset, even if we may sometimes lack the mindset at an individual level.

Using environmental concerns as an illustration, we can observe that a holistic, interdependent, resilient and sustainable worldview[80] is urgently needed for continued human existence.[81] Climate scientists recognize that economic systems are interconnected with social and environmental systems such that an imbalance in one system produces imbalances in all systems.[82] Yet science-based adaptation and mitigation solutions appear to build upon existing paradigms related to efficiency rather than interdependency.[83] For example, the Fourth National Climate Assessment Vol. 2 greenhouse gas emission mitigation measures include “emissions pricing (that is, GHG emission fees or emissions caps with permit trading), regulations and standards (such as emission standards, technology requirements, and building codes), subsidies (for example, tax incentives and rebates), and public funding for research, development, and demonstration programs.”[84]

Native oral traditions provide a holistic framework that better emphasize interdependency and valued relationships between humans and the natural environment. The “Seven Grandfather” or “Grandmother Teachings” originate in a story that it is a human responsibility to practice and balance seven interrelated and interconnected gifts to walk a good path in life.[85] The power of framing narratives should not be undervalued or underestimated: “stories are not separate from theory; they make up theory and are, therefore, real and legitimate sources of data and ways of being.”[86] The Seven Teachings, translated from original languages, are gifted wisdom, love, respect, humility, honesty, bravery and truth as one’s responsibility in all things.[87] “All” includes the business realm.[88] Each Teaching is a value, a virtue, and a character strength[89] that has its own Native meaning.[90] Unlike virtue ethics,[91] the Seven Teachings are balanced and practiced together.[92] It is important that no Teaching is left out, as it could cause one to practice the negative and opposite of that Teaching.[93]

Although each of the Seven Teachings seems to be in short supply today, perhaps there is a spark of hope. The Business Roundtable radically revised its “Statement on the Purpose of the Corporation” on August 19, 2019 when it released a comprehensive stakeholder perspective.[94] “Over three-quarters of CEOs (76 percent) say that their organization’s growth will depend on their ability to navigate the shift to a low carbon, clean technology economy.”[95] Sustainability is a strategic priority throughout the business community, including energy, manufacturing, hospitality, housing, fashion, insurance, investors and money managers.[96] It is also an opportunity for innovation in industries seeking sustainable solutions, including innovations rooted in older and more holistic wisdom traditions.

The remaining question is still: how can we combine the potential of pervasive data gathering with the holistic wisdom of aboriginal governance? It may help to offer a simple, yet profound, mental model: a diagram associated with open systems theory—an accepted, time-tested reflection of reality in many disciplines from biology to sociology.[97] In introducing this model to this area of legal scholarship, we answer the call for fresh mental models for addressing the shortcomings of law to catch-up and adapt to the twenty-first century’s societal, economic, and physical realities.[98] Such a wake-up-call to the legal profession was recently provided by the Head of the World Economic Forum.

Legal scholarship has broadly considered what systems thinking has to offer in terms of re-conceptualizing law.[99] For example, authors Luigi Russi and John D. Haskell discuss the relevance of systems theory in their critique of an overly consumerism oriented legal system.[100]

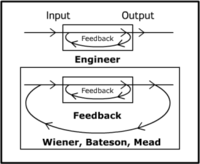

We would specifically like to introduce the feedback model as a conceptualization that could help organize both self-regulation and public policy approaches to pervasive data collection and usage in business. It is an adaptation of Katz and Kahn’s open systems model, which in turn, was inspired by Wiener, Bateson, and Mead’s modeling of feedback loops, reproduced below.

Figure 1: A Classic Depiction of a Feedback Loop

According to Bateson and Mead in a 1973 interview, this diagram illustrates the conception of an entity and ecosystem as a single circuit.[101] It reflects the simple, generalized observation that entities in various context affect their environment, which in turn has effects on the entities.[102]

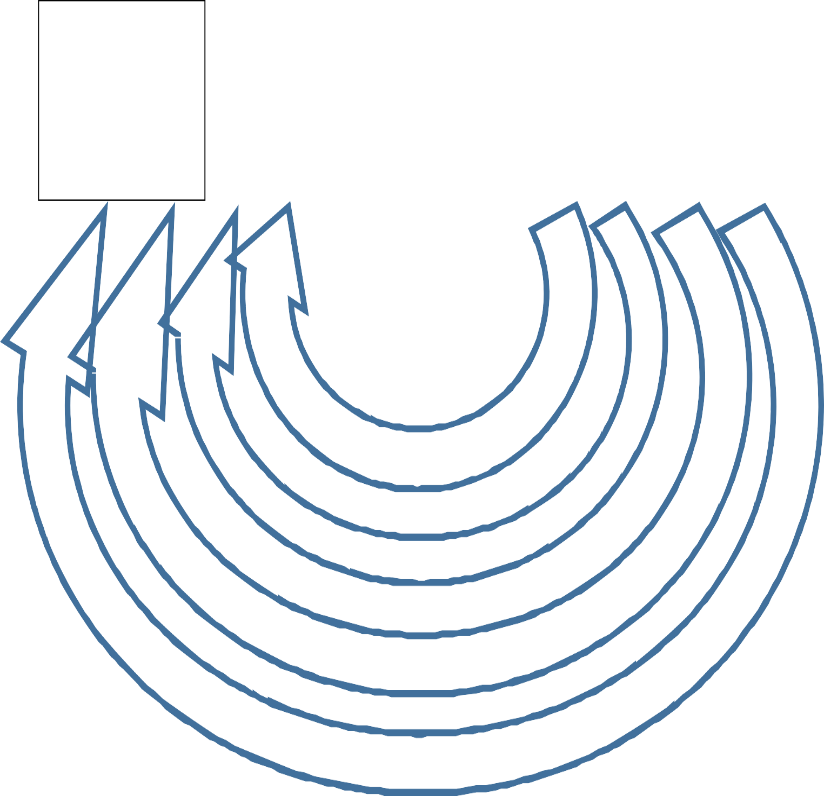

Our adapted open systems model is similar, building upon this visual representation of this general truism, adapted to the context of business: namely, that entities such as businesses take inputs and, because of throughputs, generate outputs. The feedback about those outputs may be directed back as an input to affect the functioning of the entity.[103] Our model further includes four concentric areas in which the firm operates: a legal and regulatory ecosystem, industry ecosystem, society, and natural environment.[104]

Natural Ecosystems

Stakeholders

Industry

Law

Outputs

Products, Services, Externalities & Returns on Investments

Inputs

Energy, Materials, Labor, Capital, Information from Feedback Loops

i

Throughput

Firm

Data Feedback Loops

Figure 2: Data Feedback Loops and Ecosystems, Stakeholders, Industry, and Law

The innermost ecosystem surrounding the firm—the medium through which it interacts and impacts and resolves its relationships with the natural environment, society, and its competitors and collaborating firms—is the legal and regulatory ecosystem.

The model is relevant to understand how advances in data collection and usage can “close the information feedback loop” and help management see how outputs and externalities impact inputs upon which the firm relies. To elaborate: the value of this model is in framing the positive function of ESG data reporting and technologies, if they can be used in a manner consistent with Native wisdom—that is, to consider longer-term future impacts of actions and decisions undertaken in the present.

To be sure, no model or concept on its own is without limitations. One foreseeable critique of the utility of feedback loops is that it will not solve every problem related to information. To be sure, this is not a silver bullet solution to the intentional creation and sharing of misinformation for political advantage or profit. Misinformation is beyond the scope of this essay. It suffices to say, however, that feedback loops are still relevant idea to the problem of deadly epidemics of misinformation. For illustrative purposes, a case could be made that, had the establishment of the Republican Party leadership (for years) more clearly seen the feedback loops signaling a likely eventual threat to their lives, some may have intervened earlier and more forcefully when aligned news media outlets repeated untrue factual statements leading up to the armed insurrection on January 6, 2021. We argue that monitoring feedback loops is helpful to foreseeing (and addressing) the creation of deadly alternative realities through misinformation.

Another foreseeable critique of feedback loops within the scope of this essay—collection and use of data—is that we arguably already have them, albeit imperfectly, in slow motion, and with a massive time delay. In other words, that it is already a design feature in the American approach to regulation and collective action through public policy. We typically legislate after a crisis becomes clear. For example, consider the infrastructure failures of Hurricane Katrina, the financial crash of 2008, and lack of preparation and delayed response to the unfolding COVID-19 crisis in early 2020. In all these cases, governmental U.S. systems did respond, but actions were retroactive rather than proactively based on leading indicators. From environmental calamities to societal unrest to supply chain disruption, earlier warning indicators are evident to those monitoring the right data—from climate change modeling to data on societal inequalities and demographics, to simple modeling of business processes given different assumptions.

Business decisions, lawmaking, and government actions tend to respond to, rather than anticipate, crises.[105] For example, in 2020, the COVID-19 crisis exposed a blind spot of capitalism: the failure to calculate and prepare for the long-term led to the private health care system’s failure to stockpile even the cheapest and most basic equipment—most glaringly, this equipment included seventy-five cent, protective facemasks.[106] Although the EU’s precautionary principle and the proactive law movement indicate that, at least in theory, European countries attempt to be more anticipatory, the COVID-19 crisis has shown that they were not radically different in planning for a readily foreseeable systemic risk.

The point of the last paragraph is that few, if any, human organizations—in the private or public sector—have been adequately proactive. Most, if not all, large organizations failed to gather relevant data, monitor, anticipate, and prepare. Countries that seem to have fared the best in protecting lives, as of 2021, were prompt and ruthless in gathering and using data to localize and isolate those who could transmit the novel coronavirus. Commonly cited examples include South Korea[107] and Taiwan.[108] To reiterate, this is exactly the kind of constructive combination of proactivity, holism, policy, and constructive use of data collection and usage that we are advocating. To take one example: this simple-but-profound difference in mindset led to taking elemental early steps like Taiwan stockpiling masks and building public buy-in, contributing to fewer deaths—by several orders-of-magnitude.[109]

Examples of constructive use of feedback loops in the context of big data to enable better human decisions rather than manipulation for profit are not limited to some developed countries. Peru may have suffered high rates of infection and mortality, but the population may have fared worse if not for the attempt to make real time data more accessible via mobile phones.[110] If there is one object lesson of the first months of the COVID-19 crisis for business leaders, their attorneys, and policy-makers, it is to be more anticipatory and more vigilant and proactive in collecting, monitoring, and acting upon data.

The goal of this section is to describe how leaders in the private and public sectors could take specific steps based on our model of feedback loops.

First, some of the best practices related to sustainability reporting and distributed ledger technologies described above should be considered. This could mean voluntary steps for private sector leaders—the “so what” of feedback loops is that management should deliberately establish systems and practices that could accelerate and encourage the consideration of data on impacts when planning next steps.

This could also mean the consideration of regulatory nudges or mandates from public sector leaders through public policy to consider impacts when planning next steps. Through legislation or regulatory agencies, the option exists of forcing decision-makers to take steps as a condition of operating. While manifestations of this idea exist—such as environmental impact assessments before granting permits—they appear in limited contexts, are slow, and can have their effectiveness limited.[111] In contrast, technology married to a renewal of holistic awareness could—correctly steered—improve our ability to collect and act upon data could yield an updated version of the Native wisdom described above: to consider impacts before decisions are made.

The foregoing argument—that data gathering-and-usage can be steered to constructive ends—lends further urgency to many questions that already surround the gathering and usage of data.

For data gathered about people: should more steps be required to assure informed consent, as is the case with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)?[112] Some argue that existing data-gathering platforms, from the Google Suite to Facebook, are too essential to functioning in today’s world and that, as essential services, they should be run like public utilities,[113] or else that government intervention is needed to create stronger “opt out” options to protect user privacy.[114] For law scholars, this should rekindle our interest in exploring whether the quaint notions of contracts of adhesion and unconscionability are really moribund, or could be reinvigorated and used to reassert individual privacy in this context. Given the recent decision of the U.S. Department of Justice to pursue antitrust claims against Alphabet (better known as Google), the notion that Big Tech may finally face a reckoning in the courts no longer seems theoretical.[115]

Next, if blockchain-enabled technologies can better assure the reliability of actionable data, can and should private blockchains be required, as a means of data tracking, with a public agency having access to a node to verify that there is no fraud?

More broadly, should data be destroyed periodically (not kept indefinitely), and what data should never be kept? Should a threshold be set, as with OSHA rules,[116] for the minimum size of the firms that are obligated to measure and use data? To borrow an example from the context of FMLA, should small-to-medium-sized businesses—defined as less than 50 employees—be generally exempted from certain statutory requirements?[117] For example, should there be potential corporate governance regulations that require greater gathering-and-use of data? The greater collection and use of data entail a greater risk that private data will be disclosed intentionally, unintentionally, or even as a result of extortion schemes, creating risks that attorneys should continually reassess.[118]

Should steps be mandated beyond a simple, year-end “report card” of vital stats of impacts on people and the environment? Is it a desirable policy to require the purchase of carbon credits to offset—that is (in theory) to counter or neutralize—emissions?[119] Should we attempt to mandate “net zero harm” in terms of environmental harms? Countries that already require reporting may soon foreseeably require automated offsets.[120]

The automated offsetting of harms is not limited to the environmental context. Societal offsets do exist—affirmative action programs are the most obvious example. Given the efforts to elect more women to corporate boards and diversity and inclusion efforts, it is not a stretch to imagine automating aspects of human resources practices to offset perceived or actual disparities in opportunities between demographic groups. This could give rise to renewed controversies which lawyers could proactively prepare for now.

The regulation of data collection-and-usage should not just be limited to prohibitions but could articulate what ought to be done. We have offered a way to conceptualize, consistent with Native wisdom, how existing means of gathering-and-using data could be married to the renewed holistic awareness of how businesses affect systems to accelerate and even automate the proactive consideration of impacts to render better outcomes. In the meantime, counsel should become aware of—and recommend—best practices for the gathering and utilization of data. It can be framed as a better way to fulfill fiduciary duties and reduce-or-eliminate the risk of accusations of negligence.

- † Adam J. Sulkowski is an associate professor of law and sustainability at Babson College. He received his JD & MDA from Boston College. Danielle Blanch-Hartigan is an associate professor of natural and applied sciences at Bentley University. She received her MPH from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and her Ph.D. and MA from Northeastern University. Caren Beth Goldber is an associate professor of management at Bowie State University. She received her Ph.D. from Georgia State University. Amy K. Verbos is an associate professor of business law and indigenous ethics at University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. She received her Ph.D. from University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and JD from University of Wisconsin Law School. Maoliang Bu is an associate professor of business at Nanjing University and is a visiting Professor at Ivey Business School. He received his Ph.D. from Nanjing University. Remy Michael Balarezo Nuñez is an associate professor of strategy at Universidad de Piura. He received his Ph.D. & M.Sc., Complutense University of Madrid. ↑

- .See Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism 16 (2019). (Separately-but-distinctly, and most controversially, leaked documentation by Edward Snowden showed that agencies of the federal government of the United States similarly had been collecting more data related to communication than previously acknowledged. It should be recognized immediately that there is some overlap and cooperation between surveillance by private sector entities and government; Snowden was, after all, a contractor, and hence indicative of the government’s reliance on contracts with businesses to perform its data collection. Similarly, revelations concerning the role of Cambridge Analytica and Facebook in targeting and influencing voters in 2016 raised concerns on the role of data collection-and-use in the arena of politics. This article does not address data collection and usage by governments, political campaigns, or non-profit entities. This analysis and discussion focuses exclusively on businesses, and the legal framework that could be applied to steer the conduct of businesses as they collect and use data that they collect in furtherance of their missions as profit-seeking entities.) ↑

- .See Adam J. Sulkowski & Sandra Waddock, Midas, Cassandra & the Buddha: Curing Delusional Growth Myopia by Focusing on Thriving, 61 J. Corp. Citizenship 15, 33 (2016). ↑

- .John Laidler, High Tech is Watching You, Harv. Gazette (Mar. 4, 2019), https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/03/harvard-professor-says-surveillance-capitalism-is-undermining-democracy/ [https://perma.cc/3ADX-6CYS]. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Shoshana Zuboff, You are Now Remotely Controlled, N.Y. Times (Jan. 24, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/24/opinion/sunday/surveillance-capitalism.html [https://perma.cc/MR8F-828W]. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .See Alex Engler, Tech Cannot Be Governed Without Access to its Data, Brookings (Sept. 10, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2020/09/10/tech-cannot-be-governed-without-access-to-its-data/ [https://perma.cc/526X-GZGN]. ↑

- .Jason Morgan, The New Structure of Sin: Mankind in the Age of Surveillance Capitalism, 46 Human Life Rev. 42 (2020). ↑

- .Zuboff, supra note 6. ↑

- .Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar & Aziz Z. Huq, Book Review Economies of Surveillance, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 1280, 1307 (2020) [hereinafter The Age of Surveillance Capitalism] (a book review of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power by Shoshana Zuboff). ↑

- .See Debora Jeske & Kenneth S. Shultz, Using Social Media Content for Screening in Recruitment and Selection: Pros and Cons, 30 Work Emp. & Soc’y 535, 535–37 (2016). ↑

- .See generally Chad H. Van Iddekinge et al., Social Media for Selection? Validity and Adverse Impact Potential of a Facebook-Based Assessment, 42 J. Mgmt. 1811, 1812 (2016). ↑

- .See Kevin E. Henderson, They Posted What? Recruiter Use of Social Media for Selection, 48 Org. Dynamics 1, 2 (2019). ↑

- .See Philip L. Roth et al., Political Affiliation and Employment Screening Decisions: The Role of Similarity and Identification Processes, 105 J. Applied Psych. 472 (2020). ↑

- .See Caren Goldberg et al., The Effects of Religion on the Evaluation of Social Media Profiles in Hiring, J. Applied Psych. (forthcoming 202X); Jennifer Delarosa, From Due Diligence to Discrimination: Employer Use of Social Media Vetting in the Hiring Process and Potential Liabilities, 35 Loy. L.A. Enter. L. Rev. 249, 262 (2015); Philip Roth et. al, Assessing Facebook Profiles of Job Candidates: Opening Pandora’s Box, London Sch. Econ. Bus. Rev. (May 13, 2020), https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2020/05/13/assessing-facebook-profiles-of-job-candidates-opening-pandoras-box/ [https://perma.cc/VQ7V-CCKE]. ↑

- .See Roth, supra note 15; Goldberg, supra note 16; see also Steven Rothberg, 19.3% Fewer Employers Using GPA to Screen Candidates, Coll. Recruiter (May 17, 2021), https://www.collegerecruiter.com/blog/2021/05/17/19-3-fewer-employers-using-gpa-to-screen-candidates/ [https://perma.cc/QTZ9-QAYP]. ↑

- .Chad H. Van Iddekinge et al., supra note 13, at 1811. ↑

- .42 U.S.C. § 2000e (1964). ↑

- .See Julia Angwin et al., Dozens of Companies Are Using Facebook to Exclude Older Workers from Job Ads, ProPublica (Dec. 20, 2017, 5:45 PM), https://www.propublica.org/article/facebook-ads-age-discrimination-targeting [https://perma.cc/6Z9G-TXLN]. ↑

- .See, e.g., Larson et al., These Are the Job Ads You Can’t See on Facebook If You’re Older, ProPublica (Dec. 19, 2017), https://projects.propublica.org/graphics/facebook-job-ads [https://perma.cc/K5KW-672W]. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Bradley v. T-Mobile US, Inc., No. 17-CV-07232-BLF, 2019 WL 2358972 (N.D. Cal. June 4, 2019). ↑

- .Abhimanyu S. Ahuja et al., The Impact of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine on the Future Role of the Physician, PeerJ. 1, 3, 11–12 (Oct. 4, 2019), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6779111/ [https://perma.cc/4DZQ-3BGJ]. ↑

- .Skyler Place et al., Behavioral Indicators on a Mobile Sensing Platform Predict Clinically Validated Psychiatric Symptoms of Mood and Anxiety Disorders, J. Med. Internet RES. 2 (2017). ↑

- .The IHI Triple Aim, Inst. For Healthcare Improvement, http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx [https://perma.cc/85G9-9RN2] (last visited Oct. 12, 2021); Harpreet S. Sood et al., Leveraging Health Information Technology to Achieve the Triple Aim, Commonwealth Fund (Jan. 5. 2016), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2016/leveraging-health-information-technology-achieve-triple-aim [https://perma.cc/YA7B-9MB5]. ↑

- .See W. Nicholson Price II, Risks and Remedies for Artificial Intelligence in Health Care, Brookings (Nov. 14, 2019), https://www.brookings.edu/research/risks-and-remedies-for-artificial-intelligence-in-health-care/ [https://perma.cc/8GAL-R8XF]. ↑

- .See George E. Thibault, Humanism in Medicine: What Does it Mean and Why is it More Important than Ever?, Acad. Med. 1074, 1074–75 (2019). ↑

- .See generally id. (“[W]e must see that our educational processes afford more opportunities to express and develop humanism. These opportunities include caring for underserved populations . . ., more focus on the social determinants of health, and a strengthening of the social contract . . . .”). ↑

- .The Consumerization of Healthcare, Adobe (Feb. 2019), https://www.adobe.com/content/dam/acom/en/industries/healthcare/pdfs/adobe-econsultancy-2019-report-the-consumerization-of-healthcare.pdf [https://perma.cc/7NK3-VX3Y]. ↑

- .See Salman Bin Naeem & Rubina Bhatti, The Covid‐19 ‘Infodemic’: A New Front for Information Professionals, 37 Health Info. & Libr. J. 233, 233 (2020). ↑

- .Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou et al., Addressing Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media, 320 J. Am. Med. Ass’n 2417, 2417–18 (2018); Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou et al., Where We Go From Here: Health Misinformation on Social Media, S3 Am. J. Pub. Health S273 (2020). ↑

- .See Michelle Pannor Silver, Patient Perspectives on Online Health Information and Communication With Doctors: A Qualitative Study of Patients 50 Years Old and Over, 17 J. Med. Internet Rsch. 1, 2 (2015). ↑

- .See Walter H. Henricks, “Meaningful Use” of Electronic Health Records and its Relevance to Laboratories and Pathologists, 2:7 J. Pathological Informatics 1, 2 (2011). ↑

- .See Electronic Medical Records/Electronic Health Records, CDC https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/electronic-medical-records.htm [https://perma.cc/H5GH-VEQD] (last viewed Mar. 3, 2020). ↑

- .See Linda Girgis, Why Doctors Are Losing the Public’s Trust, Physician’s Wkly. (Dec. 18, 2017), https://www.physiciansweekly.com/doctors-losing-publics-trust/ [https://perma.cc/GPB3-ZFQE]. ↑

- .Sumi Sinha et al., Disparities in Electronic Health Record Patient Portal Enrollment Among Oncology Patients, 7 J. Am. Med. Ass’n. Oncology 935, 936 (Apr. 8, 2021), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/article-abstract/2778094 [https://perma.cc/7W4A-LSEY]; Daniel M. Walker et al., Exploring the Digital Divide: Age and Race Disparities in Use of an Inpatient Portal, 26 Telemedicine & E-Health 603, 603 (2019); Sandra Gittlen, Digital Technology Adoption Depends on EHR Interoperability, New Eng. J. Med. Catalyst Innov. in Care Deliv. 1 (Apr. 2021). ↑

- .See Michael Matheny et al., Artificial Intelligence in Health Care, Nat’l Acad. Med. 1 (2019). ↑

- .FDA, Digital Health Innovation Action Plan, U.S. Food & Drug Admin. 1, 5, https://www.fda.gov/media/106331/download [https://perma.cc/H637-S5DF]. ↑

- .See generally Sharyl J. Nass et al., Beyond the HIPAA Privacy Rule: Enhancing Privacy, Improving Health Through Research (Nat’l Acad. Sci. et al. eds., 2009). ↑

- .See generally Ahuja et al., supra note 24. ↑

- .See Matheny, supra note 38; Milena A. Gianfrancesco et al., Potential Biases in Machine Learning Algorithms Using Electronic Health Record Data, 178 J. Am. Med. Ass’n. Internal Med. 1544, 1544 (2018). ↑

- .See U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., GAO-21-519SP, Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities 1, 42 (2021), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-519sp.pdf. ↑

- .Irene Y. Chen et al., Treating Health Disparities with Artificial Intelligence, Nature Medicine 16, 16–17 (Jan. 13, 2020), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-019-0649-2 [https://perma.cc/N84J-ZM94]. ↑

- .The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, supra note 11, at 1311–12. ↑

- .See Archon Fung et. al., The Political Economy of Transparency: What Makes Disclosure Policies Effective? 1 (2004). ↑

- .Sulkowski & Waddock, supra note 2, at 15. ↑

- .Fung et. al., supra note 46, at 1. ↑

- .See David Weil, The Effectiveness of Regulatory Disclosure Policies, 25 J. Pol’y Analysis & Mgmt. 155, 156 (2006). ↑

- .Id. at 156. ↑

- .See Adam J. Sulkowski & Sandra Waddock, Beyond Sustainability Reporting: Integrated Reporting Is Practiced, Required & More Would Be Better, 10 U. St. Thomas L. J., 1060, 1062 (2013); see also Adam J. Sulkowski, City Sustainability Reporting: An Emerging and Desirable Legal Necessity, 33 Pace Env’t L. Rev. 278, 279 (2016). ↑

- .Sulkowski, supra note 51, at 280. ↑

- .Fung et al., supra note 46, at 19. ↑

- .Michael Greenstone et al., Mandated Disclosure, Stock Returns, and the 1964 Securities Act Amendments, 121 Quarterly J. Econ. 399, 399 (2006); Carol J. Simon, The Effect of the 1933 Securities Act on Investor Information and the Performance of New Issues, 79 Am. Econ. Rev. 295, 295 (1989); see, e.g., Christine A. Botosan, Disclosure Level and the Cost of Equity Capital, 72 Acct. Rev. 323, 323 (1997); see, e.g., Robert M Bushman & Abbie J. Smith, Financial Accounting Information and Corporate Governance, 32 J. Acct. & Econ. 237, 237 (2001). ↑

- .Paul M. Healy & Krishna G. Palepu, Information Asymmetry, Corporate Disclosure, and the Capital Markets: A Review of the Empirical Disclosure Literature, 31 J. Acct. & Econ. 405, 405 (2001); see, e.g., Ray Ball, Infrastructure Requirements for an Economically Efficient System of Public Financial Reporting and Disclosure, Brookings-Wharton Papers on Fin. Serv. 127, 127 (2001); Bushman et al., supra note 54, at 237. ↑

- .Weil, supra note 49, at 169. ↑

- .Fung et al., supra note 46, at 24. ↑

- .Weil, supra note 49, at 159. ↑

- .Bradley C. Karkkainen, Information as Environmental Regulation: TRI and Performance Benchmarking, Precursor to a New Paradigm?, 89 Geo. L.J. 257, 321 n. 269 (2001). ↑

- .Weil, supra note 49, at 171. ↑

- .Id. at 172. ↑

- .Sidney M. Wolf, Fear and Loathing About the Public Right to Know: The Surprising Success of The Emergency Planning and Community Right-To-Know Act, 11 J. Land Use & Env’t L. 217, 234 (1996). ↑

- .Daniel C. Esty & Quentin Karpilow, Harnessing Investor Interest in Sustainability: The Next Frontier in Environmental Information Regulation, 36 Yale J. on Reg. 625, 633 (2019). ↑

- .See id. ↑

- .Theodore Charles Langlois, A Visual Data Analysis of the Toxics Release Inventory (Aug. 2018) (M.S. thesis, Clemson University) (on file with Clemson Libraries), https://www.proquest.com/docview/2117667875?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. ↑

- .See Sulkowski & Waddock, supra note 51, at 1063. ↑

- .See generally Christopher J. Hughey & Adam J. Sulkowski, More Disclosure = Better CSR Reputation? An Examination of CSR Reputation Leaders and Laggards in the Global Oil & Gas Industry, 12 J. Acad. Bus. & Econ. 1, 2 (2012). ↑

- .But see Jia Wu, Linxiao Liu & Adam J. Sulkowski, Environmental Disclosure, Firm Performance, and Firm Characteristics: An Analysis of S&P 100 Firms, 10 J. Acad. Bus. & Econ. 73, 73 (2010). ↑

- .See Adam J. Sulkowski et al., What Aspects of CSR Really Matter: An Exploratory Study Using Workplace Mortality Data, J. Acad. Bus. and Econ. (2012). ↑

- .Sulkowski & Waddock, supra note 51, at 1076; see also Sulkowski, supra note 51, at 283. ↑

- .90% of S&P 500 index® companies publish sustainability / responsibility reports in 2019, Governance & Accountability Inst. (July 16, 2020), https://www.ga-institute.com/news/press-releases/article/90-of-sp-500-index-companies-publish-sustainability-reports-in-2019-ga-announces-in-its-latest-a.html?no_cache=1 [https://perma.cc/TA57-YSH2]. ↑

- .Adam J. Sulkowski, Blockchain, Business Supply Chains, Sustainability, and Law: The Future of Governance, Legal Frameworks and Lawyers?, 43 Del. J. Corp. L. 303, 303 (2019) [hereinafter Blockchain, Business Supply Chains]. ↑

- .Adam J. Sulkowski, The Tao of DAO: Hardcoding Business Ethics on Blockchain, 3 Bus. & Fin. L. Rev., 146, 146 (2020) [hereinafter The Tao of DAO]. ↑

- .See Joan MacLeod Heminway & Adam J. Sulkowski, Blockchains, Corporate Governance, and the Lawyer’s Role, 65 Wayne L. Rev. 17, 18 (2019); see also Gerlinde Berger-Walliser et al., Using Proactive Legal Strategies for Corporate Environmental Sustainability, 6 Mich. J. Env’t & Admin. L. 1, 3–4, (2016) (providing an overview of the topic of proactive law). ↑

- .Adam J. Sulkowski et al., Shake Your Stakeholder: Firm Initiated Interactions to Create Shared Sustainable Value, 31 Org. & Env’t. 223, 223 (2018). ↑

- .Adam J. Sulkowski, Industry 4.0 Era Technology (AI, Big Data, Blockchain, DAO): Why The Law Needs New Memes, 29 Kan. J. L. & Pub. Pol’y, 1, 1 (2019); see also id. ↑

- .This section focuses on Native Nations in what is now the United States of America. Carma M. Claw et al., American Indian Business: Principles & Practices 142–48 (Deanna M. Kennedy et al., eds. 2017) (applying Diné (Navajo) ethics and the Seven Grandfather Teachings to business practice); Winona LaDuke, All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life 1 (2016) (speaking of the 150-year holocaust in which species and Indigenous peoples have become extinct; it also points to a more sustainable future); see, e.g., Gregory Cajete, Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence 14 (2000) (beginning by defining Native science “as a metaphor for Native knowledge and creative participation with the natural world in both theory and practice”). Other Indigenous traditions around the world hold similar values. Cf. Amber Nicholson et al., Ambicultural Governance: Harmonizing Indigenous and Western Approaches, 28 J. Mgmt. Inquiry 31, 31 (2019); Chellie Spiller et al., Paradigm Warriors: Advancing a Radical Ecosystems View of Collective Leadership from an Indigenous Māori Perspective, 73 Hum. Rel. 516, 516 (2020). ↑

- .See, e.g., Cajete, supra note 77, at 64. ↑

- .See, e.g., Bryan M. J. Brayboy et al., Looking Into the Hearts of Native Peoples: Nation Building as an Institutional Orientation for Graduate Education, 120 Am. J. Educ. 575, 578–87 (2014); see Amy Klemm Verbos et al., Native American Values and Management Education: Envisioning an Inclusive Virtuous Circle, 35 J. Mgmt. Educ. 1, 10 –22 (2011); Cajete, supra note 77, at 58–63; see LaDuke, supra note 77. ↑

- .If Paris Accord goals are met, due to carbon-cycle feedback loops, the climate could warm 5° C. by 2100, posing an existential threat to organized civilization. See David Spratt & Ian Dunlop, Breakthrough National Center for Climate Restoration, Existential Climate-Related Security Risk: A Scenario Approach 6 (2019). See also David Reidmiller et.al., U.S. Global Change Res. Program, Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II 25, 26 (2018) [hereinafter Climate Assessment II]; Paul Gilding, Breakthrough Nat’l. Ctr. for Climate Restoration, Climate Emergency Defined: What is a Climate Emergency and Does the Evidence Justify One? 11–13 (2019) (citing recent climate science to build a case that this is an emergency that threatens a mass extinction event by 2100), https://www.breakthroughonline.org.au/publications [https://perma.cc/T2MV-23AK]. ↑

- .Climate Assessment II, supra note 80, at 25–32, 80–82 (Look to Summary Finding No. 3 “Interconnected Impacts.” Other summary findings warn about water shortages, severe changes to ecosystems, species extinctions, harm to Indigenous peoples, extreme weather and fires, and that the Paris Climate Accord is insufficient). ↑

- .See generally Nick Watts et al., The 2020 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Responding to Converging Crises, 397 The Lancet 129, 129–70 (2021). ↑

- .Climate Assessment II, supra note 80, at 1350. ↑

- .Anishinaabe (the original people of the Odawa Nation, also called Ottawa, and Ojibwé Nation, also called Chippewa) and Neshnabék (the original people of the Bodéwamik Nation, also called Potawatomi) tell the Seven Grandfather or Grandmother Teachings: for thousands of years prior to colonialism, these human responsibilities in relationship to each other and all things guided the people to know what was good and right, and how to live in relationship with each other and all things created. The authors note that the oral tradition has no single author, and, as noted by Zooey Wood-Salomon, whether the Teachings are referred to as Grandfather or Grandmother Teachings depends upon who is doing the telling. Eddie Benton-Banai, The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway 60–66 (2nd ed. 2010) [hereinafter SEVEN TEACHINGS]. Interview with Amy Klemm Verbos, Faculty Member of Management Doctoral Student Association, The PhD Project (Sept. 2013); see Amy Klemm Verbos & Maria Humphries, A Native American Relational Ethic: An Indigenous Perspective on Teaching Human Responsibility, 123 J. Bus. Ethics 1, 2–3 (2014). ↑

- .Bryan McKinley & Jones Brayboy, Toward a Tribal Critical Race Theory in Education, 37 Urb. Rev. 425, 430 (2005) (showing indigenous philosophy is often dismissed but is as valid as any other ethical philosophy); Margaret Kovach, Indigenous Methodologies 94–102 (2009). ↑

- .SEVEN TEACHINGS, supra note 84; see also Verbos & Humphries, supra note 84. ↑

- .Claw et al., supra note 77, at 146. ↑

- .See Verbos & Humphries, supra note 84; see also id. at 145 (practicing the Teachings such as generosity, compassion, trustworthiness, taking only what one needs and sustaining all things created creates other values). ↑

- .Claw et al., supra note 77, at 147 (showing as an example that respect is not just for others, but also for all things created, animals, plants, rocks, waters, Earth, and fire); Verbos & Humphries, supra note 84. ↑

- .For example, Aristotelian virtue ethics include certain moral virtues that an individual might practice and in doing so achieve a balance (too much or too little not being virtuous), but do not specify which virtues one must practice reaching eudemonia, becoming a moral exemplar. Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics 61, n.25 (J. Sachs trans., Focus ed., 2002). ↑

- .7 Grandfather Teachings, Tribal Trade https://us.tribaltradeco.com/blogs/teachings/7-grandfather-teachings [https://perma.cc/HX4T-UAZY] (last visited Oct. 12, 2021); Claw et al., supra note 77, at 142; see also Claw et al., supra note 77. ↑

- .Claw et al., supra note 77, at 146; Verbos & Humphries, supra note 84. ↑

- .The Business Roundtable, an organization comprised of CEOs of major U.S. corporations from across sectors first put shareholder primacy into its corporate governance statements in 1997. Twenty-two years later its Revised Statement on the Purpose of the Corporation appears to reflect business concerns over the destruction wrought by that doctrine. See e.g., Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘An Economy That Serves All Americans’, Bus. Roundtable (Aug. 19, 2019), https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans [https://perma.cc/A6NE-9SBB]. ↑

- .In January and February 2019, KPMG surveyed 1,300 CEOs from 11 leading world economies across 11 business sectors. See KPMG Int’l., Agile or Irrelevant, Redefining Resilience: 2019 Global CEO Outlook 4–23 (2019), https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2019/05/kpmg-global-ceo-outlook-2019.pdf [https://perma.cc/62WF-4QCZ]. Other key issues identified by KPMG are disruptive technologies, cyber threats, conflicting views on the global economy, the need to drive organization-wide, digital reinvention, promote continuous adaptation and change, and CEOs that can navigate uncertainty, adapt, and challenge the status quo. ↑

- .See A-Rated Sustainability, 30 Corp. Citizen 32, 32–36 (2019); see also Euromoney Institutional Investor PLC & Am. Int’l Grp., AIG Creates Chief Sustainability Officer Role, Reactions, (July 24, 2019) (on file with the University of Colorado Boulder-CO); Kelly Gilblom, Big Money Starts to Dump Stocks That Pose Climate Risks, Bloomberg (Aug. 6, 2019, 10:01 PM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-07/big-money-starts-to-dump-stocks-that-pose-climate-risks [https://perma.cc/YV3E-6AY3] (explaining money managers are beginning to demand climate actions in the companies in which they invest); see also Annie Massa, BlackRock Puts Climate at Center of $7 Trillion Strategy, Bloomberg (Jan. 14, 2020, 1:43 AM), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-14/blackrock-puts-environmental-sustainability-center-of-strategy [https://perma.cc/PKR5-RGX7]. ↑

- .Alfonso Montuori, Systems Approach, 2 Encyclopedia Creativity 414, 414–21 (2011), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123750389002120 [https://perma.cc/6H2F-ZEQX]. ↑

- .Cf. Sulkowski, supra, note 69 (identifying the shortcomings of existing metrics and opportunity for scholars to add value to the real world by testing theoretical and practical connections between CSR metrics and company performance and financial value; a measure enabled by a systems approach). ↑

- .See, e.g., Luigi Russi & John D. Haskell, Heterodox Challenges to Consumption-Oriented Models of Legislation, 9 Unbound: Harv. J. Legal Left 13, 13 (2015). ↑

- .Id. at 40–47. ↑

- .Gregory Bateson, Env’t & Ecology, http://environment-ecology.com/biographies/546-gregory-bateson.html [https://perma.cc/2WUS-HJQE] (last visited Oct. 12, 2021). ↑

- .Karl Johan Åström & Richard M. Murray, Feedback Systems: An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers 1 (2008), https://authors.library.caltech.edu/25062/ [https://perma.cc/EK2H-NNUV]. ↑

- .See id. ↑

- .Some argue that society can be further subdivided into stakeholders (shareholders, employees, and consumers) and shapeholders (regulators, the media, and social and political activists), with the latter group’s power being underestimated by many managers. See Mark R. Kennedy, Shapeholders: Business Success in the Age of Activism 18 (2017). ↑

- .Rob A. DeLeo, Anticipatory Policymaking: When Government Acts to Prevent Problems and Why It Is So Difficult 202 (2015). ↑

- .Farhad Manjoo, How the World’s Richest Country Ran Out of a 75-Cent Face Mask, N.Y.Times (Mar. 25, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/25/opinion/coronavirus-face-mask.html [https://perma.cc/8KBY-A6BJ]. ↑

- .Timothy Huzar, COVID-19: What can we learn from South Korea’s response?, Med. News Today (Aug. 18, 2020), https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/covid-19-what-can-we-learn-from-south-koreas-response [https://perma.cc/M6YF-LXA4]. ↑

- .Cindy Sui, What Taiwan can teach the world on fighting the coronavirus, NBC News (Mar. 13, 2020, 9:17 PM), https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/what-taiwan-can-teach-world-fighting-coronavirus-n1153826 [https://perma.cc/WR97-BKXS]. ↑

- .Id. ↑

- .Plataforma digital única del Estado Peruano, Gobierno lanza nueva versión de app “Perú en tus manos” para advertir a los ciudadanos sobre las zonas con mayor probabilidad de contagio [Government launches new version of the app” Peru in your hands” to warn citizens about theareas most likely to beinfected] (May 7, 2020), https://www.gob.pe/institucion/pcm/noticias/150943-gobierno-lanza-nueva-version-de-app-peru-en-tus-manos-para-advertir-a-los-ciudadanos-sobre-las-zonas-con-mayor-probabilidad-de-contagio [https://perma.cc/RC5T-FPA9]. ↑

- .See Adam J. Sulkowski, Ultra Vires Statutes: Alive, Kicking, and a Means of Circumventing the Scalia Standing Gauntlet in Environmental Litigation, 24 J. Env’t. L. & Litig. 75, 75–119 (2009). ↑

- .See GDPR Resources & Information (2018), https://www.gdpr.org [https://perma.cc/2YHP-X3MT]. ↑

- .IT Solution Singapore, Social Media Networks Becoming Internet Public Utilities: Is it Considerable? IT Sol. (Nov. 15, 2019), https://www.itsolution.com.sg/news/should-google-and-facebook-become-public-utilities/ [https://perma.cc/RJ5X-WJ3J]. ↑

- .Nicole Ozer & Chris Conley, After the Facebook Privacy Debacle, It’s Time for Clear Steps to Protect Users, ACLU (Mar. 23, 2018, 12:00 PM), https://www.aclu.org/blog/privacy-technology/internet-privacy/after-facebook-privacy-debacle-its-time-clear-steps-protect [https://perma.cc/UQ5J-8CHA]. ↑

- .See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t Just., Justice Department Sues Monopolist Google For Violating Antitrust Laws (Oct. 20, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-monopolist-google-violating-antitrust-laws; Brent Kendall & Rob Copeland, Justice Department Hits Google With Antitrust Lawsuit, Wall St. J. (Oct. 20, 2020, 8:08 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/justice-department-to-file-long-awaited-antitrust-suit-against-google-11603195203 [https://perma.cc/WE6B-M67X]; Keris Lahiff, Google under fire: What the DOJ’s lawsuit means for Alphabet, CNBC (Oct. 21, 2020, 7:09 AM), https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/21/google-antitrust-lawsuit-what-doj-attack-means-for-alphabet-stock.html [https://perma.cc/8RX3-TFQV]. ↑

- .OSHA’S Recordkeeping Rule, U.S. Dep’t Labor (Feb. 19, 2015), https://www.osha.gov/recordkeeping2014/; 1904.1 – Partial exemption for employers with 10 or fewer employees., U.S. Dep’t Labor, https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1904/1904.1 [https://perma.cc/S4EV-QQVB] (last updated Feb. 18, 2020). ↑

- .Anniken Davenport, Under 50 employees? How FMLA could apply to you regardless, Bus. Mgmt. Daily (June 7, 2021), https://www.businessmanagementdaily.com/9999/under-50-employees-how-fmla-could-apply-to-you-regardless/ [https://perma.cc/648D-XUDN]. ↑

- .Adam J. Sulkowski, Cyber-Extortion: Duties and Liabilities Related to the Elephant in the Server Room, 1 J. L., Tech. & Pol’y 101, 102 (2007). ↑

- .Sean Fleming, What is carbon offsetting?, World Econ. Forum (June 14, 2019), https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/06/what-is-carbon-offsetting/ [https://perma.cc/3B64-GAGQ]. ↑

- .Id. ↑